Jocelyn Edward Greville Stevens was born on Valentine's Day 1932. He came from a privileged background but had a strange and unhappy childhood after his mother, the daughter of newspaper proprietor Sir Edward

Hulton, died soon after giving birth. His father, Major Greville Stewart-Stevens, sent the small boy away to live in his own flat in London with a staff to look after him. Jocelyn Stevens spoke about this early part of his

life when he was the ‘castaway’ on the BBC's Desert Island Discs in March 1992.

Jocelyn was educated at Eton and, after National Service in the Rifle Brigade, attended Trinity College, Cambridge. When he reached 21 he inherited a large sum of money from his late mother and although featuring regularly in

the society gossip columns as a ‘man about town’ he also found time to attend a course at the London School of Printing and began work as a journalist at Lilliput, a magazine owned by his uncle.

In 1956 Stevens married Jane Sheffield, a lady-in-waiting to Princess Margaret, and, shortly after, bought himself a 25th birthday present - his own magazine, Queen. Originally launched in 1861 as “The Queen”

by the husband of the Victorian cookery writer Mrs. Beeton, Jocelyn dropped the definite article from the masthead and revamped the publication to make it popular with the young trendy people then known as the ‘Chelsea

Set’. His editor Beatrix Miller drew up a style sheet for the magazine. In it she described the young, female, good looking target reader. She gave this fictitious woman the name ‘Caroline’

(see timeline). It has been suggested that this could have been the origin of the later radio station's name. Stevens appointed his friend Mark Boxer (cartoonist Marc) as Art Director of the

magazine which frequently featured the work of photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, later to marry Princess Margaret and become Lord Snowdon.

By all accounts Stevens wasn't an easy man to work with or for. The More About Advertising website has

described him as a “combination of Bertie Wooster and Genghis Khan”; the satirical magazine Private Eye nicknamed him “Piranha Teeth”; the Daily Telegraph obituary (see below) recalls that when he

became chairman of English Heritage in 1992, one commentator said it was “like putting Herod in charge of childcare”. It seems Jocelyn quite enjoyed having this fearsome reputation.

Around Easter 1963 a hustling young Irishman called Ronan O'Rahilly met a friend-of-a-friend called Ian Ross and told him of his plan to launch an offshore radio station. Ian thought that his father might be

interested in investing. O'Rahilly visited Ross senior, who introduced him to another possible investor, businessman John Sheffield. Sheffield then brought in his son-in-law, Jocelyn Stevens. They all decided to put money into the

venture and, although Jocelyn was not one of the larger investors, he became a director of Planet Productions, the station's sales company. It was decided to call the station Radio Caroline.

|

|

|

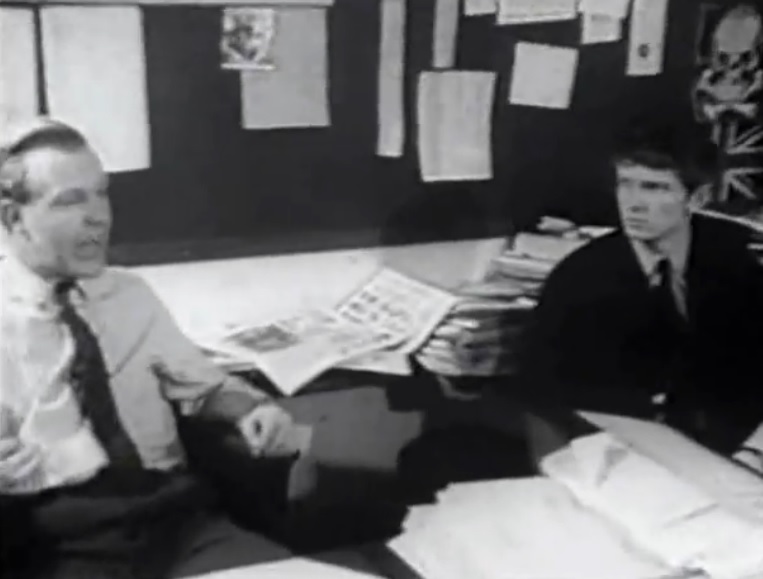

Jocelyn Stevens, left, and Ronan O'Rahilly on Granada TV's ‘World In Action’ in May 1964.

|

Stevens was heavily involved with Caroline in its early days. The new offshore broadcaster shared the Queen offices in London's Fetter Lane and Jocelyn was often called upon to act as a spokesman,

taking the lead role in Granada TV's World In Action programme about the pirates broadcast in May 1964. He was responsible for employing a number of the early station personnel, including Michael Parkin the sales

director. But once the station had taken off and moved into its own offices in Caroline House, he kept a lower profile, leaving Ronan O'Rahilly to be the public face of Caroline.

In 1968 Jocelyn Stevens sold Queen. He became personal assistant to the chairman of Beaverbrook Newspapers, Sir Max Aitken. He went on to have a long career in newspapers - with the Evening Standard, the Daily Express and helping to launch the Daily Star - before moving into the arts as Rector and Vice-Provost of the Royal College of Art and then chairman of English Heritage.

In 1992 Radio Caroline's last ship, mv Ross Revenge, was languishing in Dover harbour after being salvaged from the Goodwin Sands. A short-term ‘Restricted Service License’ was granted for the station to broadcast

legally on FM. A microwave link was used to send the output from a studio on the ship to the transmitter located at Dover Castle. One of the station's advertisers was English Heritage, the agency responsible for the upkeep of the

castle, which suggests that Jocelyn Stevens, then chairman of English Heritage, may still have had some affection for his old station after nearly thirty years.

Jocelyn Stevens became Sir Jocelyn in 1996. He died on 9th October 2014*, aged 82. The newspaper obituaries listed below mainly concentrate on his career in publishing and the arts but those of us who were fans of Radio Caroline will always be grateful to him for the investment and energy that he brought to the station back in the sixties.

Alan Turner worked for Radio Caroline in 1964:

“I met Jocelyn Stevens I think twice, once in the Queen offices and again in Caroline House. He was a live-wire and got things done. He had an assuredness that comes from

having real family wealth behind him. I don't think Caroline would have been the first had it not been for his involvement. None of us involved in the early days had any idea of what was to come from what we were starting.”

|