|

|

|

| Paul Burnett out on the deck of Radio 270's ship, the mv Oceaan VII. This photo courtesy of Roger Scott. More of his photos are here. |

Back in the eighties Steve England and his friend Leon Tipler were planning to put together a documentary about Radio 270.

Sadly it was never completed but some interviews were carried out for it, including this one with Radio 270 Breakfast DJ Paul Burnett.

At the time of the interview Paul was working for BBC Radio One and Steve spoke to him in the station's then headquarters, Egton House, in London.

They met on 10th August 1982. Please note that some of the comments that Paul made at the time (for instance about Wilf Proudfoot, Boots Bowman and Radio Luxembourg) are now out of date.

We are very grateful to Steve for sharing the recording with The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame.

STEVE ENGLAND: How did you get involved with Radio 270?

PAUL BURNETT: Well I was resident DJ at the Top Rank in Darlington. It was called The Majestic and I'd just come out of the air force - no actually I was still in the air force, that's right. I'd been for two years in Aden and

I'd done some sort of radio, rather like some fellows do hospital radio - just as a hobby - but it was a little radio station out in the Middle East and I'd, in my spare time, spent many hours down there. And when I came back to

Britain in '65 I got a night time job moonlighting as a Top Rank DJ in Darlington but I was in the air force during the day at RAF Dishforth which was just down the A1. Then someone came up and said “there's a pirate ship

starting off the north-east coast” and so I applied for it and with the little experience I had - which I sort of dressed-up a bit, you know, made out I was Programme Controller or something, I really did spin a yarn - I got

the job. And actually it was funny because I got the job and I'd forgotten I was still in the air force. It was my last year in the air force and because I enjoyed the DJ-ing so much I just sort of began to look upon the air force

side of things as a bit of a chore I had to do during the day and I'd forgotten all about the fact that I couldn't really go out on a ship because I was still in the air force. I remember it hitting me as I walked away thinking

“great, I've got the job” suddenly realising I had this slight commitment to her majesty. So I had to buy myself out. I only had six months to do and I had to buy myself out. £125 it cost me. My mother cashed her

Premium Bonds, bless her. I bought myself out.

SE: And who was on board? Were you there at the start?

PB: Well yes, it had a false start actually because the ship was due to start broadcasting on April 1st 1966 and we - a whole bunch of us - were in a hotel in Scarborough waiting for the word to go out and meet the ship which was

coming up from Great Yarmouth[1] where it had been fitted out. It was all a very last minute thing and we got the word at about 1 o'clock in the morning to go out. We went out on a trawler at 1 o'clock in

the morning from Scarborough and sailed down the coast to meet it. It was all very romantic, very clandestine, except I was as sick as a pig and I thought “hello, what have I let myself in for?”. We actually met the ship at dawn. I remember it coming

over the horizon. It was quite a stirring sight. It was an impressive boat, ours. It wasn't big. It was only 150 tons and the (aerial) mast was longer than the actual length of the boat. It had a little sail on the back as well. It

was an old Dutch lugger which had been fitted out. We had to get on board at about 5 o'clock in the morning and between 5 o'clock and going on air at midday we had to get a library sorted out, get all the records filed, and we worked

like beavers. Just about 10 o'clock, as we were steaming up past Bridlington on our way to take up our position off Scarborough, the worst storm in about ten years blew up off the coast and it wrecked the ship. I mean it was a genuine

shipwreck. So we never got on the air but the funny thing was that they had a big reception in one of the best hotels in Scarborough, and our boss was there with the press and everything, and they had transistor radios all over this

room, and of course we couldn't let them know that we weren't going on the air. And of course it was April 1st so the press actually walked out thinking it was a really bad taste joke! So there we were, unable to let them know that we

weren't going on the air - and it was obviously going to be months before we got on the air because the mast snapped off; it had to be cut off. It was waving around the ship like a huge pendulum, smashing into the bridge. It was really

a shipwreck job. We had the lifeboats out and everything. I was very depressed about it because I thought “hello, that's the end of the dream”. I got the train from Scarborough and went home to Darlington, which was my home

then. I bought the Evening Dispatch and, on the placard was “local man in shipwreck drama”. I bought the paper and there was a picture of me - I've still got the press cutting - “local man in shipwreck drama”,

telling how the ship had been wrecked prior to going on the air. Anyway the upshot of all that was we didn't get on the air until several months later.

SE: I didn't realise you lived in Darlington.

PB: Well my mother was living in Darlington.

SE: I thought you were from Manchester.

PB: I was born in Manchester, yes, but my parents were variety artists. I lived in a caravan and travelled all over. They just happened to end up there really.

SE: Was you father a band leader?

PB: Yes, he still is. He's in Blackpool right now. He's a Musical Director and Dickie Henderson's accompanist when he goes abroad. Stuff like that. So I had a kind of variety background but my parents divorced when I was about 12.

SE: Who was on board (Radio 270) when you joined?

PB: Oh well, there were names that I don't suppose would mean anything because none of them went on to do other things, except Mark Wesley. Mark Wesley - ex-Radio Luxembourg, he was on the ship but that was just after I left. He

joined from Radio City[2], one of the pirate forts, and I think he called himself Mark West then. I remember the names but they wouldn't mean anything to you -

Hal Yorke, Mikey Mo - they all had funny names like that.

SE: I am putting this together with Leon Tipler...

PB: Leon Tipler! Well he'll tell you about the shipwreck. He was on the ship when that happened.

SE: I have got some names here. Can you tell me a little bit about them? Noel Miller?

PB: Oh Noel Miller. Yes. He's a butcher in Australia now. I got a letter from him about a year or so ago. He's left radio. He was our station director actually and one of the two guys who'd had some experience: him and Dennis the

Menace, Dennis Straney. Very impressive guys. They were from Sydney, from a station called 2UE which is a very hot-shot station there. We didn't know it at the time but I understand they'd only been in

radio for about six months themselves (laughing) but they'd grown up with commercial radio so they knew so much more than we did, and I'm very grateful to them[3]. We learned a lot off them. They really

taught us about format radio, Top 40 radio, which was new to Britain at that time.

SE: What was the tender like?

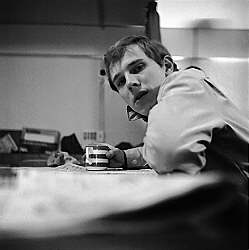

|

|

| Paul in his bunk on board the mv Oceaan VII. Photo courtesy of Guy Hamilton. |

PB: (Groans) Well it was funny because... Radio 270 was made up of... Everybody who was on the board, you know, the board of directors (contributed something)... Put it this way, the tendering was done by Bill Pashby,

Commander Bill Pashby, who had a fleet of trawlers so on their way out fishing they would drop us DJs off and, on their way back from a fishing trip, they'd pick us up and run us in. There was a farmer (on the board of directors) called

Roland Hill. He was a farmer so he provided the provisions for the ship - vegetables and all the rest of it. Wilf Proudfoot - he was the head man - he was an MP and still is I understand, the Conservative MP for

Cleveland[4]. He was the boss of the whole thing but also ran a chain of supermarkets so he provided canned goods, things like that. There was a man whose name escapes me but he ran a newspaper in Scarborough

so he looked after press; and we also had an amazing man called Don Robinson who was a wrestling promoter - very sharp man - actually he was a wrestler himself[5]. He's a millionaire now. He on the board,

one of the directors of Yorkshire Television I think. But he did all the stunts because that was his business with the wrestling. He provided all the publicity and also booked the gigs. Things like that. So it was a clever little set-up.

Every bloke (board member) had a part to play, but the tendering was done, as I say, by Bill Pashby but there was a bust-up in the boardroom and he pulled out, leaving us without a tender. We were (stuck) out there for about three weeks.

Wilf Proudfoot just went out and bought a little rowing boat; put an engine on the back of it. It was only about 15 foot long. We were out in the North Sea, in an open rowing boat, with a motor on the back of it. How we didn't perish

I'll never know.

SE: Leon told me about it. Is that the one you refused to go out on?

PB: Yes, we refused to go out on it. The funniest thing is it actually only made one trip. I was on the trip coming out with Wilf - he came out with us. There were about six of us in this little boat and we reached the boat and then

a storm blew up so they couldn't go back. So they had to stay the night on board. The next morning when they woke up there was this piece of rope hanging down the back of the ship with just the prow of this little boat, you could see

about 2 ft. under the water. It had sunk. It had been smashed against the side of the boat and broken into a hundred pieces. So they - we had a radio, a ship-to-shore telephone by then - and they had to radio for another boat to come

out. After that we didn't need a tender because they had this great idea of just going off the air and sailing in once a week. We used to sail into Bridlington harbour. All the lights out; change over, then sail out again; and three

miles out, all the lights would come back on again and we'd start broadcasting again. We did that every week.

SE: Every week?

PB: Yes. Every week. I think ours was the most piratical of the lot.

SE: How about the crew?

PB: Initially we had a Dutch crew and, believe it or not, they actually do wear wooden clogs - just like you see in the films - and one of the radio engineers who was a bit of a jack-the-lad, when one of those guys - and those blokes

were big - when one of those guys was up the mast and he'd left his clogs on the deck, the wooden deck, he got these 6" nails and hammered the clogs into the deck. They looked just normal, just slightly apart, and this guy came shimming

down the mast, slipped his feet into his clogs, tried to walk away and nearly broke his ankles. It really hurt him. He sprained his ankles. He was hobbling around for days afterwards. He got his own back though because he threw the

bloke overboard when he found out who it was. Just threw him overboard. That's the clog saga.

|

|

| Paul on the mv Oceaan VII. Photo courtesy of Hal Yorke. More of his photos are here. |

SE: How did the Oceaan 7 take the weather?

PB: Oh, it didn't. It rolled like a pig. I mean a ship like that was never meant to be moored in a static situation. In fact whenever the weather got rough we had to up-anchor and ride into the storm, you know, with the engines going

so that we'd keep the same position. Whereas the ship could roll as much as it liked, it wouldn't affect the turntables because they were set into gimbals. It is very hard to explain but it was like the turntables were set into a table

top that is suspended on a two-way hinged table so that the ship can roll all over the place but you could leave a cup of tea on that turntable and it wouldn't spill a drop. But when the engines were running then you got vibration and

I've got some tapes of Radio 270 and it's hilarious because the records are all a-a-a-a-a (wavering) like that - fast vibrations which you couldn't cope with. The whole ship vibrated and every time there was a storm, that's when you

could tell. I could always tell when there was a storm when I was on shore by just the way the records sounded, you know.

SE: What were the Radio 270 nights out like?

PB: Well really they were the forerunner of the Radio One-type roadshow, you know. We did one in Bridlington which was a big night out, at the Bridlington Town Hall I think, but, no, the biggest night of all - I think Leon Tipler

would remember this - the biggest night of all was in Leeds, at the old tram sheds in Leeds which are now called... something[6], I don't know, it's just a vast hall and we had The Who topping the bill. It

was just around My Generation time. They were smashing their instruments up and everything. We had two stages, which was great,

and there was also a fun fair inside this hall - you can see how big it was - and a barbecue. It was an all-nighter. Jimmy Savile was there. Oh it was really exciting. We just went up and announced each band. There was Sounds

Incorporated, Pinkertons Assorted Colours and top of the bill was The Who, and they just went wild. Fabulous night that was.

SE: What sort of area did the station cover?

PB: Well it was really only blocked in by the Pennines. It got as far north as, well, the Scottish border and as far south as Lincoln and down there. We'd do gigs all over - Hull, Lincoln, Leeds, you know - the Radio 270 Nights Out.

That's when I first started doing gigs as a name DJ.

SE: It must have been very exciting.

PB: Oh, it was.

SE: Can you tell me about some of the other more obscure people...

PB: Boots Bowman was the... I - and I think all of us - thought that he would, of any of us, be a big success. He was very creative in the same way as Kenny Everett. A

very similar type actually because, although you wouldn't know it now, Kenny - talking to people who worked with him on the (Radio London) ship - was a very introverted sort of person and would only come alive when he was actually on

the air, and the same was with Boots Bowman. You know, a very shy, quiet bloke but very popular. He was possibly the most popular DJ on 270. I don't know what happened to him after the ship closed down but he called me up a few months

ago and he's a manager of a hotel here in London.

SE: Can you describe the layout of the ship?

PB: Yeah. It's indelibly printed on my memory. We'll start aft, as they say. At the back end there we had some showers and sort of ablutions and what have you; and then the studios, there were two of them. The ship was about 20 ft. wide

I think - not big, is it? - 20ft. wide and next to the studios was the main salon which was the width of the ship and about 30ft. long. About three (bunk) beds were arranged either side - I'd be better drawing you a map - and these were all

screened off with curtains so we had some privacy - and in the centre was a long table which went across the boat with seats, fixed, so we ate and slept in the same room. Then next to that was the galley. Then you'd have to go up the

ladders on deck and then down to the crew's quarters which were very cramped right at the front, in the pointed end. And that was basically it.

SE: And what was the normal complement of people on board?

PB: Um, I think about 5 DJs at one time and a technical bod, about 5 crew and Captain and a cook. That would be about it.

SE: How did you come to leave the station? Did you leave before August 14th 1967?

|

|

| A photo of Paul from his time with Manx Radio. Paul is top left. Anticlockwise from Paul: Don Allen, Bob Stewart and

George Ferguson. Photo taken from the (defunct?) Manx Radio Nostalgia website. |

PB: Yes I did. It's the only thing I can honestly claim any credit for, although it sounds like leaving the sinking ship, but I really did want a career in radio and I knew that come September '67[7] all the

ships were going to close down. We knew that was going to happen. And I figured that there were going to be hundreds of blokes looking for maybe ten jobs, you know. I wanted to stay in radio very much so I got an agent. I'd been trying

for the other ships - I wanted to get on Radio London, Radio Caroline - and this agent came up with a vacancy on Manx Radio. By this time I was Programme Controller on Radio 270 and I was earning £35 a week which in 1967 was a

lot of money and I took this job for £22 a week at Manx Radio, because it was legitimate radio. I went in March 1967. I left 270 and went to Manx Radio and it was the best move I ever made because of course I would have been on

the ship in September '67[7] and gone the way of most of them. I was there for six months on Manx Radio and I was heard by somebody from Radio Luxembourg and I was offered a job in Luxembourg.

SE: What was Manx like when you were there?

PB: Oh that was terrific - hard work though - I did seven hours a day on the air. I did four hours in the morning, the Breakfast Show, for six days a week and, for four of those days, I would do a three hour show in the afternoon as

well. And in between that we'd go and interview people in shops and things. They really made you work hard but it was good experience - and we'd do commentaries on the TT and power boat racing round the island. You were a jack of all

trades. It was good experience but bloody hard work. (Laughing) I was not unhappy to leave there to go to 208. I mean, 208 was a magic number. I thought that was almost as good as the BBC - which it was then. It was then. It was very

glamorous then.

SE: What were the conditions like on Luxembourg?

PB: Oh well you were up there with the Pete Murrays and the David Jacobs and all that in those days, '67. I'm talking about October '67 now. There was no station that could give you that kind of prestige that Luxembourg gave you then

and every night your own show, with you own name on it. Luxembourg does that with unknown people whereas Radio One tends to do that with established people, which is the way it should be, although they are now taking people from local

radio who are not known nationally. Luxembourg is a good grounding for Radio One because it's pretty much the same sort of set-up: there's just a bloke with a pile of records left to his own devices really. And doing discos, expected

to do a certain amount of PR for the station.

SE: Were you in the Grand Duchy?

PB: Yes I was. Lived out there for six and a half years. We had Tony Prince, Kid Jensen, Mark Wesley, Bob Stewart - we were all together for about five years. It was a very

strong team back then.

Our thanks to Paul, and to Steve for providing the interview.

For other items kindly provided by Steve England, see the DJs' memorabilia index page.

|

|

| Paul, top left, with the rest of the Radio Luxembourg DJs in 1972. Photo from ‘Deejay and Radio Monthly’ magazine. |

NOTES

|

|

We are not sure that Paul is correct about the ship being fitted out in Great Yarmouth. Some work was done in the Netherlands with the mast and transmitter being installed in Guernsey. Maybe the

ship called into Great Yarmouth on its way north.

|

|

|

Mark joined 270 from Radio Essex, not Radio City.

|

|

|

Noel Miller writes: “I'd like to correct one thing Paul said about Dennis Straney's and my radio experience prior to Radio 270. 6 months??? Not on your nelly, mate. Both of us had done the hard yards of

working our way through Australian country radio. It was tough and competitive and both of us had followed similar paths through numerous country stations before working our way to top stations in Sydney. In my case it took 5 years.

At one stage I took over Dennis's shift at 2WG Wagga when he moved up the scale. It's a similar story for all the Australians who worked in British radio. We all went through the tough (poorly paid) melting pot of Australian country

radio because we loved it, and it was that spirit that attracted us to pirate radio.”

|

|

|

Wilf Proudfoot died in 2013. There is a tribute to him here. He was the Conservative MP for Cleveland from 1959 to 1964, and for Brighouse and Spenborough from 1970 to 1974.

|

|

|

There is a page about Don Robinson on the Wrestling Heritage website. A biography Don Robinson - The Story of a High Flier

by David Fowler is available from Amazon.

|

|

|

Probably a reference to Queens Hall, Leeds. The Who played there on 14th October 1966.

|

|

|

Paul refers to “September '67” as being the end of Radio 270. Actually it was 14th August that year.

|

|