Part One: The beginning.

Britain's first offshore station, Radio Caroline, began broadcasting at Easter 1964 but what happened before that date, in the run-up to the launch, is less well-known. In fact the precise history of

the period is clouded by PR invention, a good deal of mythologizing, some failing memories and the sad fact that most of the main protagonists are no longer around to tell their stories.

|

|

|

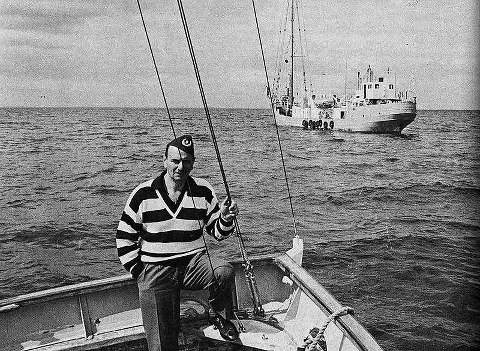

Jack Kotschack with the Swedish station Radio Nord in the background.

|

It is generally accepted that, although Radio Caroline made it onto the air first, the planning for the rival station, Radio Atlanta, pre-dated it by several years. Allan Crawford, an Australian music

publisher based in London, was frustrated by the lack of broadcast outlets for his record releases and began working on his Atlanta project as early as 1960. (See timeline and

interview with Crawford.)

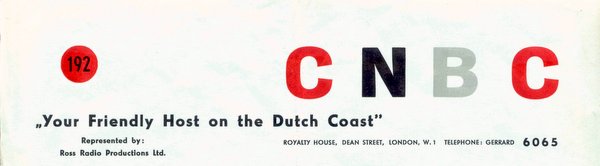

Europe's first commercial offshore station, Radio Mercur, had begun broadcasting off Denmark in 1958, followed by Veronica off Holland in 1960 and Radio Nord and Radio Syd, off Sweden, in 1961 and 1962 respectively. Veronica

had tried broadcasting to Britain with some English-language programmes under the name of CNBC (Commercial Neutral Broadcasting Company) during 1960-61 but these had not been a success. It has been suggested that it was copies

of CNBC sales literature, left in its office when the team moved out, that provided the inspiration for the next tenant, Allan Crawford, but sadly this is just another of the numerous myths that surround the early days of

offshore radio. Although both had offices in Dean Street, as can be seen from the letter-headings on this page, CNBC was based in Royalty House (nos. 72-74) while Crawford was at no. 47.

|

|

|

CNBC letter heading, kindly provided by Keith Martin.

|

Crawford followed the progress of the various offshore stations with interest and visited both Nord and Veronica. Radio Nord was the brainchild of Americans Gordon McLendon and Bob Thompson together with

Swedish-Finnish movie executive Jack Kotschack. McLendon owned US radio stations including KLIF in Dallas (later to be the inspiration for another offshore station, Radio London) and was one of the founders of Top 40

format broadcasting. Radio Veronica was run by the Verweij brothers who had made their money in the textile trade. Crawford spoke to them and took careful note of the legal loop-holes through which their stations were able

to operate. According to his interview, at one point the Verweijs offered to sell Crawford a share in Radio Veronica but nothing came of these discussions.

|

|

|

Cover of The Pilkington Report kindly provided by Colin Nicol.

|

The Pilkington Committee had been set up by the British Government in 1960 to consider the future of broadcasting in the country. In 1962 it published its report. After long deliberation it had decided

there was no demand for commercial radio in the UK. Having experienced the thriving Australian commercial radio scene at first-hand, Crawford was convinced that this was not the case. By 1962 he had raised some funding and,

when the Scandinavian Governments jointly outlawed their offshore stations, he made an offer to buy the Radio Nord ship, mv Magda Maria (previously called mv Bon Jour). The vessel was moved to the UK coast ready for him to

take over but, when the Danish authorities raided Radio Mercur and forced that station off the air, one of Crawford's main investors pulled out of the project. This scuppered the deal. Eventually the ship was taken to Texas

where McLendon planned to use the equipment for his other radio stations. (Around this time, the ship's name was changed again. She became mv Mi Amigo.)

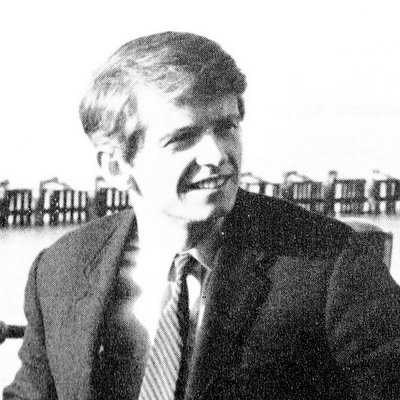

Meanwhile a young Irishman called Ronan O'Rahilly was hustling around London, getting involved in a number of projects. Since arriving from Dublin he had operated an actors' studio, run The Scene club in Soho

and dabbled in various show business ventures. He had become involved in the early careers of pop groups The Rolling Stones, through his friendship with Giorgio Gomelsky, and The Animals and, through brothers Rik and John Gunnell,

with Georgie Fame. The Gunnells ran the all-night weekend gigs at The Flamingo Club in London's Wardour Street. Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames played there regularly and won a large, loyal following. Legend has it that Ronan met

a woman at a party who told him about Radio Veronica, the Dutch offshore station. Inspired by the idea, he decided that the time was right for a British equivalent. However that story might not be completely true.

At some point, in 1962 or 63, the two future pirate chiefs met. Patrick Starling tells us that the meeting was in “a club/bar in Dansey Place, Soho”. Allan Crawford (in our

interview) claims that O'Rahilly intimated to him that his father, businessman Aodogán O'Rahilly, might be interested in investing in Atlanta and, to convince him of the viability of the project, Crawford

handed over papers containing all his market research, technical plans and legal advice – which Ronan immediately copied for his own rival project. This can't be verified but it would explain why both had such similar legal

structures and technical specifications - although, as they were learning from the experiences of earlier stations, there were bound to be some similarities.

Ronan put together a group of people to work on his new station. His friend Christopher Moore, a club DJ, provided the musical knowledge and, having served in the Merchant Navy, some nautical experience

too. Moore introduced O'Rahilly to a mate of his, Ian Ross. They met one lunchtime around Easter 1963. O'Rahilly told Ross of his plans. Ross was impressed by the project and thought that his father might be interested in investing.

Mr Ross Senior worked in the city and was an expert in raising venture capital. That afternoon they squashed themselves into Ian Ross's MG sports car and set off to the family home in Haslemere, Surrey. By that evening the deal

had been done. His father put in some of his own cash, as did his friend John Sheffield, chairman of the Norcros Group of companies. Together they and their firms put up over 80% of the launch capital - some £250,000 in all. Other

investors included Sheffield's son-in-law Jocelyn Stevens, then proprietor of Queen magazine, and Dublin lawyer Herman Good. They all recognised the plan had potential.

In 1963 the Gunnell brothers financed a recording session for Georgie Fame and his band. The story has been told that Ronan O'Rahilly had the idea for Radio Caroline while trying to promote one of the Fame tracks (named as

Let The Sun Shine In in an interview he later gave to Radio One). Having failed to get the song accepted for airplay on

either the BBC or Radio Luxembourg, then the country's only broadcasting outlets, he reasoned that the alternative was to start his own station. In fact, although this story is a perfect example of why Britain desperately

needed more music radio in the sixties, it seems likely that Ronan had already begun planning Caroline by the time he was plugging the Georgie Fame acetate.

|

|

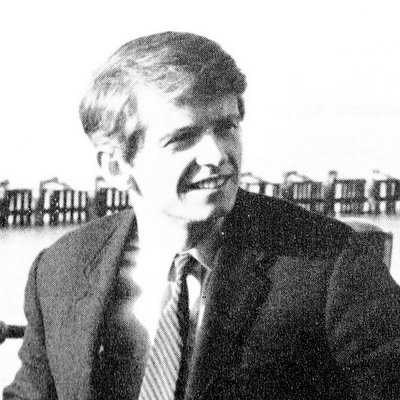

The fathers of UK offshore radio. Ronan O'Rahilly, left, and Allan Crawford.

Photos from a Caroline Club booklet.

|

O'Rahilly acquired the funding for Radio Caroline in an evening. His rival, Allan Crawford did not find it so easy to raise the backing for Project Atlanta. This was the company he had formed with

city financier Frank Broadribb, publisher and Lloyds underwriter Major Cecil Lomax, accountant William Wells and others, including his friend theatrical agent Kitty Black (see tribute). The

chairman was Major Oliver Smedley. Crawford was a cautious man. He knew he was embarking on a risky venture and he didn't want anyone to jeopardise their life savings. Unlike Radio Caroline, Atlanta's capital was raised

very slowly from a large number of small investors. “More than a hundred” people, some grouped together into syndicates, put up the cash for Radio Atlanta. One of these groups was comprised of several Trinity

House pilots. In all, about £150,000 was raised.

|

|

|

Project Atlanta letter heading, kindly provided by Colin Nicol.

|

Offshore radio researchers Mervyn Hagger and Eric Gilder have discovered that Ronan O'Rahilly initially attempted to buy the same ship that Allan Crawford was after - the mv Mi Amigo - but, when his offer was turned down,

was forced to look further afield. He obtained the former Danish ferry Fredericia. By December 1963 Project Atlanta finally had the funds to purchase the mv Mi Amigo. The ship was brought back

across the Atlantic. Since its time as Radio Nord, the old aerial mast had been removed and Crawford needed a quiet unobtrusive harbour where a new antenna could be erected. By a lucky coincidence Aodogán O'Rahilly

owned just such a port, Greenore, situated in a secluded part of Ireland, near the border with the north. Ronan O'Rahilly was concerned that, as Radio Atlanta had the advantage of owning an already converted broadcasting

vessel, it might make it onto the air first. To keep an eye on the station's progress not only did he move the Fredericia to Greenore but he also offered the port's services to Atlanta. Crawford was understandably wary of

this surprising offer but he realised that secrecy was vital and Greenore was an ideal place for the work to be carried out, far away from prying eyes. In return for the use of the harbour, Caroline was allowed time in Atlanta's

London studio. This they used for DJ training and to pre-record programmes, put together with the help of Atlanta's Australian producer Ken Evans (see tribute). This co-operation between the two rival

organisations is not quite as strange as it now seems because it had been mutually agreed that the two stations would not directly compete. It had been decided that Caroline would broadcast to northern England while Atlanta took

the south.

The Atlanta team might have had the advantage that their ship had already been converted for use as a floating radio station but O'Rahilly's family connections in the port ensured that the Fredericia continually got preferential

treatment and the Mi Amigo suffered a number of setbacks. Patrick Starling tells us that the weather played a part too: “The Mi Amigo arrived in Greenore first and tied-up against the stone quay. Spencer Rigging (who were

installing the aerial masts for both vessels) shipped the new mast from the Isle of Wight ready to install on the boat. The mv Fredericia arrived in Greenore and tied-up on the seaward side of the Mi Amigo. As fate would have it,

a storm broke out in Carlingford Lough and to minimise damage to the boats, both boats cast-off and anchored in the lough, waiting for the storm to abate. After the storm, the Fredericia tied-up alongside the quay first. This

enabled the crane on the quay to install the mast onto that ship first and she then set sail.” (Disc-jockey Simon Dee's memories of Greenore are in this article.

There are photos of the Fredericia in the harbour on the Radio London website.)

|

|

|

There's no mention of Caroline Kennedy on the cover but could a photo feature in this magazine have inspired O'Rahilly to name his station Caroline? Scan kindly provided by Colin Nicol.

|

The origin of the name Caroline is a matter of some debate. O'Rahilly has told the story that it was while flying to America to buy the transmitters for the station that inspiration struck. Leafing

through a copy of a magazine (possibly Look, Life, or The Washington Post), he came across a photo spread of the American President Kennedy in The White House. One of the photographs showed his

daughter Caroline playing in The Oval Office and disrupting the business of government. The image inspired O'Rahilly. Radio Veronica already operated under a female name (derived from VRON, the initials of Vrije Radio Omroep

Nederland, Free Radio Broadcasting Netherlands) and Radio Caroline seemed equally suitable.

The Radio Atlanta team heard a different story. They were under the impression that Ronan had named the station after Caroline Maudling, the daughter of politician Reginald Maudling, who, rumour had it, O'Rahilly was rather

keen on at the time (see Richard Harris and Allan Crawford interviews).

Mervyn Hagger and Eric Gilder have come up with a third possibility. They discovered that Beatrix Miller, the editor-in-chief of (Caroline director) Jocelyn Stevens' Queen magazine had created a style-sheet for the

publication. It listed the attributes of the ideal reader: young, trendy, bright and “with-it”, Miller had christened this perfect consumer ‘Caroline' (see timeline).

Maybe all three suggestions are correct. Could it have been the coincidence that O'Rahilly kept encountering the same name that convinced him to call his station Caroline?

|

|

|

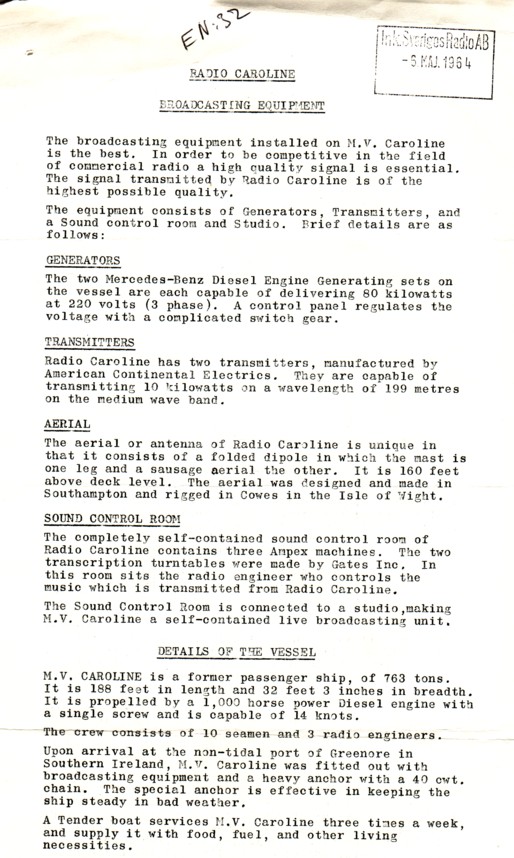

Details of the Caroline ship and broadcasting equipment kindly provided by Hans Knot. Click to enlarge.

|

On the evening of Good Friday 27th March 1964 the Fredericia dropped anchor, not in the north of England as had been agreed, but off Suffolk. O'Rahilly had seen Atlanta's audience projection figures. The

largest available listenership was in the south-east and he wanted it for his own station. Patrick Starling: “Radio Caroline did not have the benefit of the forward planning of Allan Crawford and as a result anchored

off Lowestoft. This location was too rough for an anchored ship so they moved to anchor of Felixstowe.” Precise details about the first test broadcasts are vague. Some claim that they started at about 5pm on 197.4 metres,

1520 kilohertz and that later, at 9pm, the first voice was heard. Others have claimed that the test did not begin until 11.55pm and that it was on a different frequency: 1495kHz (200.7 metres). Some have said that the first

words were spoken by Programme Director Christopher Moore but Pop Went the Pirates by Keith

Skues credits John Junkin.

The tests continued the next day on 1520kHz. On land, Ronan O'Rahilly had summoned the media to a press conference at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese in Fleet Street - but it did not go according to plan. Talking about it in

an interview with DJ Johnnie Walker in 1998, he recalled: “We had taken this restaurant in Fleet Street for the press launch ..... What we didn't know was that the restaurateur had been quite

adventurous with his heating system, so he had covered the entire restaurant in copper: the walls, the ceiling - he had copper behind the decorations to heat the restaurant. Due to this copper .... no (radio) signal could get in.

So I had this massive great Zenith (radio receiver) .... we switched it on around midday and of course - absolute silence. Nothing came through and we thought, my God, something's gone wrong .... I honestly, to this day, don't

know what made me do it but I lifted the Zenith and I walked out of the restaurant .... out into the street, followed by all the media folk. And the moment we hit the street, blasting in came the test signal, which was Ray Charles.”

The launch press release is here. Ronan again: “We kept playing Ray Charles albums because we knew that the only station that would be playing continuous Ray Charles would be Radio Caroline...” Then at

noon proper programmes began with the station theme, 'Round Midnight by Jimmy McGriff. Disc-jockey Simon Dee announced the station and introduced his colleague Chris

Moore who presented the very first programme. After his theme, I've Got A Woman also by Jimmy McGriff, he kicked off with the Rolling Stones'

Not Fade Away, although for years it was claimed, even in Caroline's official publicity material, that the first track was The Beatles' Can't Buy Me Love. Radio Caroline was on the air.

Simon Dee and Christopher Moore open Radio Caroline at 12 noon on Easter Saturday, 28th March 1964 (duration 54 seconds)

Simon Dee and Christopher Moore open Radio Caroline at 12 noon on Easter Saturday, 28th March 1964 (duration 54 seconds)

Part two of ‘Caroline in the Sixties' over the page.

|