Part Five: The North Sea fights back.

January 1966 was a bad month in the North Sea. On the 11th the Radio London ship, the mv Galaxy, dragged her anchor in a gale (see cutting). The Clacton

lifeboat was launched but fortunately its services were not required. The Galaxy's Captain and crew managed to regain control. The station was off the air the following morning because the ship had drifted

inside territorial waters. By lunchtime she had been towed back to her normal anchorage, past the rival Caroline South where Dave Lee Travis was on the air. He commented that an old warship was being towed

past “flying the surrender flag”! If he had known what the fates had in store for him and his colleagues, he might have been a bit more sympathetic. At 1pm on the 12th Radio London programmes

resumed.

Just a week later, on 19th January, Caroline South's ship, the mv Mi Amigo, also lost her anchor - and nearly came to an untimely end. It was 9pm on a very unpleasant winter's evening when the Walton-on-the-Naze

coastguard noticed that the Mi Amigo was drifting. The DJs and crew were blissfully unaware of the fact. Engineer George Saunders was on board at the time and has kindly agreed

to share his memories of that eventful night:

|

|

|

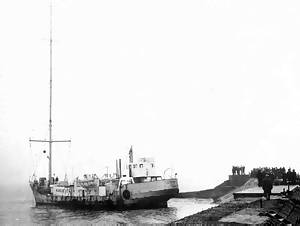

The Mi Amigo grounded. Photograph from ‘When Pirates Ruled The Waves’, published by Impulse Publications.

|

“We'd ceased broadcasting for the day. The weather was very bad - it was blowing a full gale, with driving snow and sleet for most of the time. The ship was pitching and rolling very heavily.

People moving about had to grip things to avoid being thrown.

Many of us, DJs, engineers and crew, were watching a very good TV programme about the life of pop star Donovan. Normally, when the ship swung with the tides around her anchor, someone had to climb onto the boat

deck to turn the TV aerial round to maintain the pictures. Dave Lee Travis went up to do this. He came back to the mess room with the comment “I've never seen the shore lights so

clear before, and I can't see Radio London”. At first we passed it off but he insisted we take a look. One of the Dutch crew said something and dashed up to the bridge to check our position. He found that we were

drifting. At this point in the general alarm, the TV programme ended and the ten o'clock news was about to start. The TV signal broke up again, so we switched the set off. Had we but known it, the coastguards had

noticed that we were drifting much earlier and tried all ways to alert us. But there was no bridge or anchor watch being kept. As a last resort they'd got the TV station to broadcast an emergency message - just when

we'd lost the programme!

We were well inside territorial waters. I went to the transmitter room with my fellow engineer, Carl Thomson. We took the crystals out of the transmitters and disconnected the aerial.

I put the crystals in a drawer in our cabin. By now the ship was rolling very badly - far worse than I had ever known it. The Mi Amigo had a low freeboard so her deck was now constantly swept by the sea. When she rolled

it was deeply submerged. Going down to the transmitters meant descending a long iron ladder. This time we had to hang on for dear life otherwise we would have been thrown to the bottom. The ship was rolling so badly

that water began trickling through the deck ventilators into the transmitters. There was no way of closing the vents from inside the transmitter room. We had a couple of large canvas covers which fitted externally over

the vents but the wind would have carried them (and anyone holding them) away quickly.

|

|

|

The Mi Amigo on Frinton beach. Photo from ‘Broadcasting From The High Seas’, published by Paul Harris Publishing.

|

By now our ship's engine had been started but it couldn't hold us against the heavy seas and the windage of our tall aerial mast. We'd sent out a Mayday on our ship's radio which had been answered

by the shore authorities and our tender.

I thought that there may be fatalities so I was keeping a minute-by-minute account in our loose-leaf radio log. I gave the carbon copies to (engineer) Patrick Starling for safe

keeping just before abandoning the ship and I kept the original. Carl was capable of giving a good account without notes. In the event of an official inquiry, I hoped that one version would have survived.

About 11.15 we knew that we would have to abandon ship. We put on our lifejackets. The crew told us to take up safe positions because there would be a big bump when we touched ground. We were all completely

calm. Someone looked at the mess room clock and aloud asked himself “Just think - another hour and I may be dead. Wonder what it's like?” No one said anything in reply. He'd summed up what we were all thinking.

I had crawled under the stout mess room table with a DJ - I've forgotten who it was - and we ate bowls of cornflakes while I kept the log. We ran aground at about five minutes to midnight with a very heavy bang.

Soon afterwards the coastguards fired two rockets to us and the crew prepared an escape apparatus called a breeches buoy. This was an endless rope and pulley system, stretched between ship and shore with a horizontal

lifebuoy in which we fitted ourselves, one at a time. We were then pulled to shore - and safety.

Before we left we all shook hands and wished each other well. I spoke to Graham Webb and Tony Blackburn and my fellow engineer Carl Thomson. He'd been most

helpful. Before leaving the Mi Amigo for the last time, I revisited my cabin and collected my passport, money, keys and a photo of my girlfriend. Together with the logbook, I stuffed them all into my anorak and then it

was out into the snow, water and breeches buoy.

|

|

|

Stuck on the beach. Photo from ‘Who's Who In Pop Radio’, published by Four Square Illustrated.

|

On the way across, most of us got a thorough soaking. I lost my shoes. I stumbled up the beach towards a police sergeant. He put his arm around me and said “You're all right now, lad”

and led me towards a waiting ambulance. This was almost full with the others. Some of the earlier DJs ashore had already been taken away by police car. DJ Tom Lodge brought ashore a

large bull-horn with him. On the way up the shingly beach, I saw something vaguely like fluff. I'm short-sighted and had taken my glasses off for safety. “What's that?” I asked the sergeant. “Snow,

lad” was the answer. I was so cold and disoriented that I couldn't feel a thing as my bare feet trod on it. At the top of the beach, bureaucracy was already entrenched. A very disagreeable customs officer asked

each of us if we had anything to declare! The reception he got can't be mentioned politely. We were all taken to Walton-on-the-Naze police station and put in the warm charge-room. The time was now past 1am. Here we

were given warm drinks, dry towels and excellent aid and comfort. I wondered if we were going to be charged with anything. Our heads were in a noose. The state now had both us and the ship in its grasp.

Two things happened suddenly. Firstly, an Immigration Officer arrived and checked our passports.

Secondly, the station sergeant stood on a small box and called for silence. He told us that under two Acts of Parliament we were hereby classified as ‘shipwrecked and distressed mariners’. That meant that

all our clothing which was wet was written off and that under the Acts we were allowed fresh dry clothing adequate for our lives as mariners! The police then knocked up an outfitter's shop in Walton and we received

free dry clothing!

|

|

|

Preparing to haul the Mi Amigo off the beach. Photo by Keystone from ‘Offshore Radio’, published by Iceni Enterprises.

|

We then returned to the police station. The press began to arrive and we all posed for a staged photo in the charge room (see below). Then they asked for our stories but we were so exhausted and

shocked that we agreed with practically anything they suggested. Meanwhile the police had found us accommodation in an hotel so we went there for the rest of the night. We dug in and everybody phoned relatives to

say that we were safe and well. I shared a bedroom with Patrick Starling. For the first and only time I smoked a cigarette. We were both suffering from delayed shock, with chattering teeth and shaking hands. Patrick

chain-smoked.

In the morning, after breakfast, we met the press again. One man was particularly arrogant and offensive. But the London Evening Standard sent a very nice lady reporter - excellent psychology! She probably had the

most accurate account of all (see here). The police then returned. They asked: “We've been on board the ship. Who's in charge?” My heart sank. What had they found? I put

my hand up. “Come with us, please”. There was no further explanation. Wormwood Scrubs was opening its gates. But I needn't have worried. They'd boarded the ship, searched all our cabins and put all our

personal property into whatever bag was available. All I had to do was sign for it.

We got the bags back to the hotel and had a major sort-out. No one lost too much. After that we had a few more photos in our new gear and then most of us went home by train.

Only when I saw the press photos did I realise what a lucky escape we'd had. The beach was broken up by groynes about 120 feet apart. There was only one point in the entire beach between Frinton and Clacton - five

and a half miles - where there was a gap of about 200 feet. The Mi Amigo was 133 feet 8 inches long. She'd floated over a concrete breakwater and come to rest neatly on the beach at this point, with only a few

feet to spare at each end. If she'd hit a groyne, or the breakwater, I'm told that she would probably have capsized and broken up very quickly in the storm. I'm convinced that we had a Friend in a High Place that

night.”

|

|

|

Relieved to be on land. The rescued DJs and engineers pose at the police station. George, in glasses, is in the middle.

Photograph from ‘Radio Caroline’, published by MRP Books.

|

Many thanks to George for sharing his vivid memories.

The above text is based on a script George has written for a proposed radio series

Radio Ships: Broadcasting From The Sea.

Caroline South was silenced - but only for a while. The station was soon back on the air from a borrowed replacement ship. See part six of ‘Caroline in the Sixties’ over the page.

Back to the previous page.

|