Goodbye Maurice Cole, hello Kenny Everett.

|

|

|

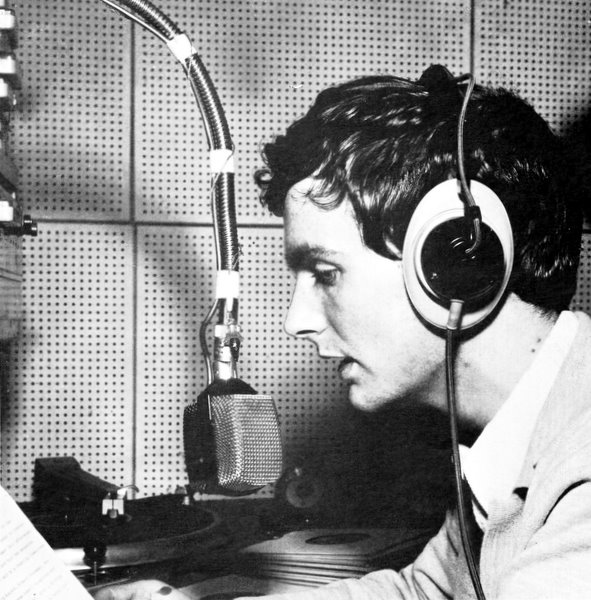

Kenny Everett in the Radio London studio. Photo courtesy of ’Beat Wave’ magazine.

|

The passing of Wilfred De'Ath on 19th February 2020, aged 82, has prompted us to look in detail at the very start of Kenny Everett's career, and the part De'Ath - and others - played in it. We are grateful to the

help of the various Kenny Everett biographies listed below.

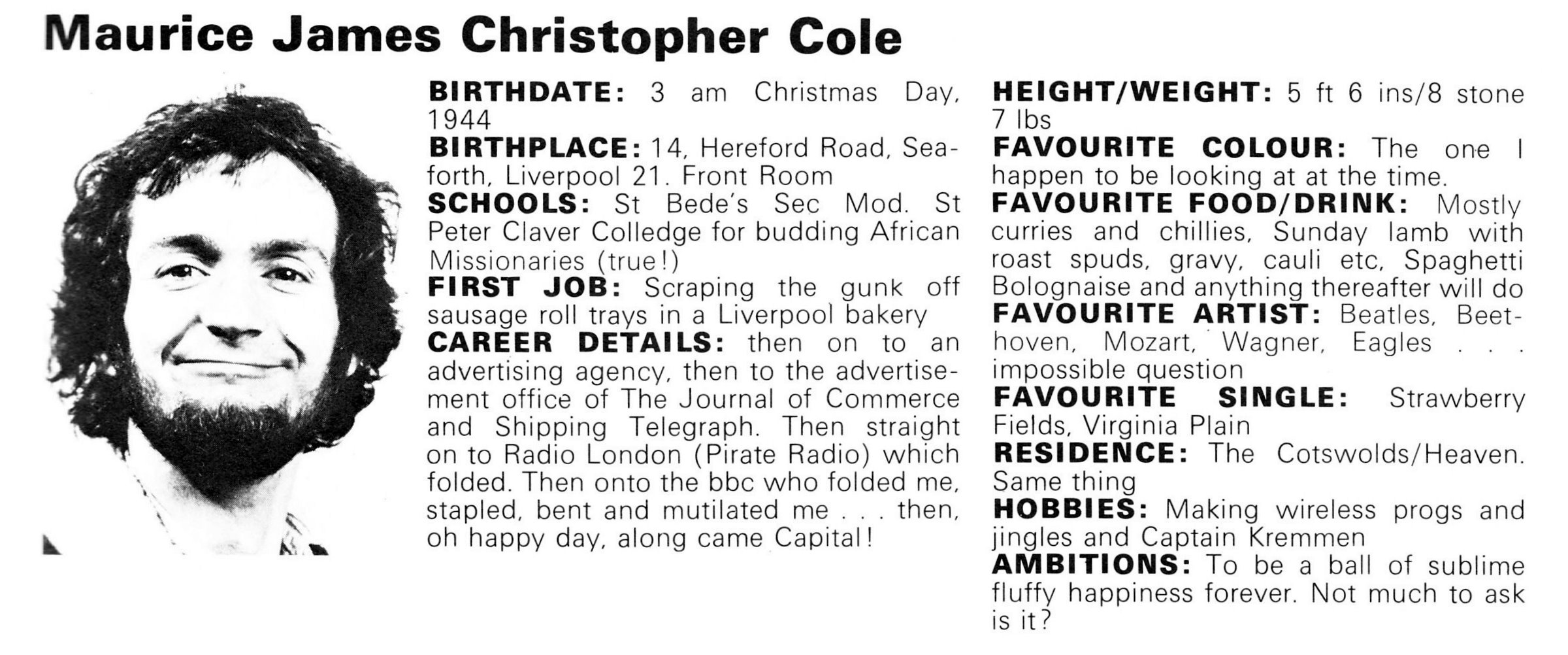

Kenny was born Maurice James Christopher Cole in Liverpool on Christmas Day 1944. He did not become known as Kenny Everett until he joined Radio London at the end of 1964 so we will refer to him by his birth name here. Maurice was not

particularly academic and left St. Bede's Secondary Modern School at the age of 15, getting a job at Cooper's, a local food shop. His position was in the bakery “scraping the gunk off sausage roll trays”, as he later

described it.

When he wasn't at work, Maurice's hobby was playing around with his tape recorder. He already had one machine, bought from the proceeds of his paper round, and now, with the money from his new job, he was able to save up enough to buy

a second. This enabled him to get creative, making little programmes, complete with jingles he sung himself.

Maurice did not enjoy his time at Cooper's. Three months of scraping sausage roll gunk was enough for him. He quit and spent a short period on the dole before being taken on by an advertising agency as a copy boy. This was far more to

his taste and he progressed up through the ranks of the company. From there he moved to the advertising department of a specialist newspaper called The Journal of Commerce & Shipping Telegraph.

|

|

|

Biographical notes from the ‘Capital Radio Funbook’, published by Capital Radio Ltd. in 1976.

|

Throughout this period of his teenage years, Maurice was playing with his tape recorders and honing his production skills. He was an avid reader of Tape Recording Magazine, in particular Alan Edward Beeby's

Tape Talk column. Beeby invited readers to send him their tapes and, in the issue dated August 1963, he mentioned one he had received from young Maurice Cole. He wrote:

“TAPE TALENT DEPARTMENT: I have some advice to offer to any talent-scout who may be reading this column. It is this: ‘When you've finished signing-up guitar-bashing, hollering teenagers with about as much talent as a

mentally-retarded orang-utan, take time out to pay a visit to young Maurice Cole who lives in Seaforth, Liverpool, 21. Take him back to the recording-studio, provide him with a tape-recorder, a record transcription deck, a pile of

records of his own choice and an editing-block. Then leave him to it. Don't try to direct, produce or stage-manage him - just leave him alone to get on with it. You'll have quite a pleasant surprise.’ How do I know about Mr.

Cole? He was among the readers who responded to my recent invitation to ‘send me a tape.’ What makes me think he has talent? My 16 years as a semi-professional variety producer - and it takes one hell of a lot to make me

sit up and beg for more! Mr. Cole just talks and plays records. Doesn't sound very original, does it? It isn't - until Maurice takes over the DJ chair. It's difficult to describe his style, but if you've ever watched and listened to

Timothy Birdsall* (TWTWTW's madcap cartoonist), you may get some idea. In my humble opinion, he's well worth a spot on ‘Sound.’ ARE YOU TAKING THIS DOWN BBC?”

(* Note: Timothy Birdsall was a British cartoonist who died young from leukaemia - in fact he died just before the publication date of this magazine. He had found fame in The Sunday Times. His work later appeared in The Spectator

and Private Eye and, as mentioned by Beeby, on BBC Television's That Was The Week That Was, or TW3 as it was known.)

|

|

The front cover of the August 1963 edition of ‘Tape Recording Magazine’ and an extract from the ‘Tape Talk’ column that mentions young Maurice Cole. Images from the

World Radio History website passed to us by Ray Clark.

|

The tape that Maurice had sent to Beeby was called The Maurice Cole Quarter Of An Hour Show (and was actually about 12 minutes long). It is not known if Maurice sent it to the BBC as well, or if Beeby passed

it on - or maybe someone at the Corporation read about it in Tape Recording Magazine and requested a copy, but it came to the attention of one Wilfred De'Ath. It is possible the tape was directed to him because he was the

youngest producer in Broadcasting House and was known to be interested in youth culture. De'Ath was preparing to launch a new show for youngsters to be called The Teen Scene. He loved the tape and was

determined to feature The Maurice Cole Quarter Of An Hour Show on his new programme. Then in spring 1964, before The Teen Scene had started its run, De'Ath was asked to cover for another producer looking after the Home

Service's Midweek. This was a magazine programme which ran for many years in different formats but at that time was just twenty minutes long, went out at 1:40pm each Wednesday and was hosted by Ronald Fletcher.

On 4th May 1964 Maurice received an invitation from the BBC to appear on Midweek. Although the David & Caroline Stafford book Cupid Stunts quotes from a letter De'Ath wrote to him, Maurice remembered it as being a telegram

that he received. In his autobiography, The Custard Stops at Hatfield, he wrote:

“I remember driving along the Dock Road (on my moped) that morning on my way to work, holding the telegram in between my thumbs on the handlebars, reading it over and over and over again, missing lorries by millimetres. I was in

a state of total euphoria, unable to believe that the BBC should not only bother to condescend to speak to me, but should send a telegram too! That morning I had my first feelings of ‘what the hell am doing working in this

dump?’ Such feelings were a little premature, so I suppressed them and wrote off to the BBC and said that I was looking forward to meeting them. They sent back details of trains and directions for getting there plus a map of

Broadcasting House, and off I trundled. Mum and Dad were, of course, over the moon because here at last was an opportunity for me to do something they could talk about in polite company. The train journey itself was a thrill: just being

on the train to London - land of June Whitfield. When I arrived at the BBC my first impression was that it was like a giant cake. I'd never seen buildings so impressive before. Everyone was so pleasant, I couldn't believe it. The

doorman told me where to go and then directed me to the office. People asked if I'd like a cup of tea, and then I met Wilfred de'Ath who told me I was a ‘find’ and I was going to be a star. He took me home, showed me his

wife, put her back in the cupboard and then poured me my first gin and tonic which tasted like perfume. (Very BBC drink, gin and tonic - they all drink G & Ts and wear Hush Puppies.) I had dinner with Wilfred and his wife, and I

remember him pointing out something that was on television about a ‘pirate radio ship’ called Radio Caroline sailing into a harbour somewhere. ‘Interesting,’ he said, ‘but it'll never last.’ I didn't

know what he was talking about, I was so far gone on his gin, and anyway all I could see was a big boat with a stick on it. I stayed in a hotel overnight, which was another thrill. The next day I woke up with my first-ever attack of

show-biz butterflies, for that was the day of The Interview. I went back to Broadcasting House and gaped at the tape machines and piles of equipment everywhere. Then I was bundled into a studio where Ronald Fletcher was going to

interview me, live! The clock's hands creaked towards the appointed time and suddenly there I was - everywhere. All over the country. I couldn't believe it. I thought: ‘Hey, this is going out to places as far afield as Herne Bay,

Ireland, Torquay. I've hit the Big Time!’ Then he introduced me briefly and played three minutes of the tape I'd sent in called The Maurice Cole Quarter Of An Hour Show. I sat listening to it again, hardly able to believe

that it was happening. Mum would be listening, Dad, (my sister) Kate, everyone I knew. Then he asked me a few more questions, like: ‘Are your parents connected with show business?’ to which I replied: ‘Oh no, they're

all quite boring really.’ My first radio faux pas, of which there were, of course, to be many, many more.”

Sadly there is no mention of Maurice's appearance in the Radio Times entry for 13th May 1964.

|

|

|

Left to right: authors James Hogg and Robert Sellers, with Wilfred De'Ath at the launch of the book ‘Hello, Darlings!: The Authorized Biography of Kenny Everett’ in 2013.

|

Wilfred was convinced that Maurice was going to be a star and suggested he should be invited for an audition at the BBC. This happened a few weeks later under the auspices of Derek Chinnery, later to become

Controller of Radio One. It was not a success and Maurice returned to Liverpool thinking his radio career was over.

For appearing on Midweek, Maurice received a fee of five guineas (£5.25) and £4/17/0d (£4.85) expenses for his train fare. The Corporation refused to reimburse him for the overnight stay in the hotel and Wilfred

De'Ath ended up having to pay for it out of his own pocket.

The first edition of The Teen Scene was broadcast on the Light Programme the following month, on 25th June 1964 at 9:30pm. The Maurice Cole Quarter Of An Hour Show was featured again but, as before, the

Radio Times makes no mention of it.

Following the failure of the Chinnery audition, De'Ath suggested Maurice should send his tape to Morris Sellar who, with his colleague Roy Tuvey, produced programmes for Radio Luxembourg, as well as writing comedy scripts, producing

records, etc..

De'Ath also told Chris Peers, a record promoter and agent, about his young discovery. We do not know if De'Ath was aware of this or whether it was pure good fortune but Sellar, Tuvey and Peers were all being consulted by

Philip Birch and Ben Toney, the Managing Director and Programme Director of the soon-to-be-launched Radio London, in their search for suitable broadcasting talent. Toney and Birch were

handed Maurice's tape. They could see there was something special about him but he was young, just 19, untried and untested. He was a bit of a risk. They decided to employ him - but on a smaller salary than his colleagues. He got

£15 a week (worth around £212 in 2020).

All the disc jockeys that joined Radio London at the start of the station had to change their names. His new surname came from a Hollywood actor, Edward Everett Horton (see

IMDB). His first name because Ben Toney told him ‘you look like a Kenny’.

From The Custard Stops at Hatfield: “Up until Radio London I'd been plain old Maurice James Christopher Cole (Mum still calls me ‘Our Mo’), but after I'd joined the pirates our great big Texan programme

controller, Ben Toney, a huge great beef of a man, came on board one day and told us that we all had to change our names for legal purposes. I've never been able to fathom out why, but I was always willing to oblige anyone who signed

cheques, so I dug around in my brain cells for a good name. I think I'd just seen a movie with an actor called Edward Everett Horton. He was a star from the Twenties to the Forties, an American comic who made loads of films and later

appeared on television as a Red Indian chief in F Troop (note: actually he played Roaring Chicken, a native American medicine man). I quite liked the name Everett so that came first, followed straightaway by Kenny. Goodbye

Maurice, 'ullo Ken.”

|