|

The Keith Martin Story

part one

|

|

Keith Martin was fascinated by radio from an early age. As a child, growing up in Kent, he scanned the radio dial for distant signals. Keith became aware of offshore

radio long before most of us in Britain had even heard of it - visiting the Danish Radio Mercur, trying to find work on the Dutch-owned CNBC, and becoming involved with the UK's earliest planned offshore stations.

The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame invited Keith to tell his story. He did this in a number of emails and telephone conversations from his home in London to his friend

Colin Nicol, in Perth, Western Australia. Colin edited them together to produce the basis of this article. Our grateful thanks to them both.

On this page we read of Keith's early interest in radio, his visit to Europe's first offshore station and his work with GBLN - a station that hoped to be Britain's first pirate, but never quite made it.

“I would not wish to be a boring old fart pouring out about being a radio ‘anorak’ in the days long before someone first misused that word, attribution for

which should be made to Andy Archer, or so I was told by him - so it must be true. Whatever, I go along with that. But, if what follows does go on and on for far too long I will now name

the names to blame: The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame who started me off and Colin Nichol who painstakingly pumped it out of me. They made me do it.

|

|

|

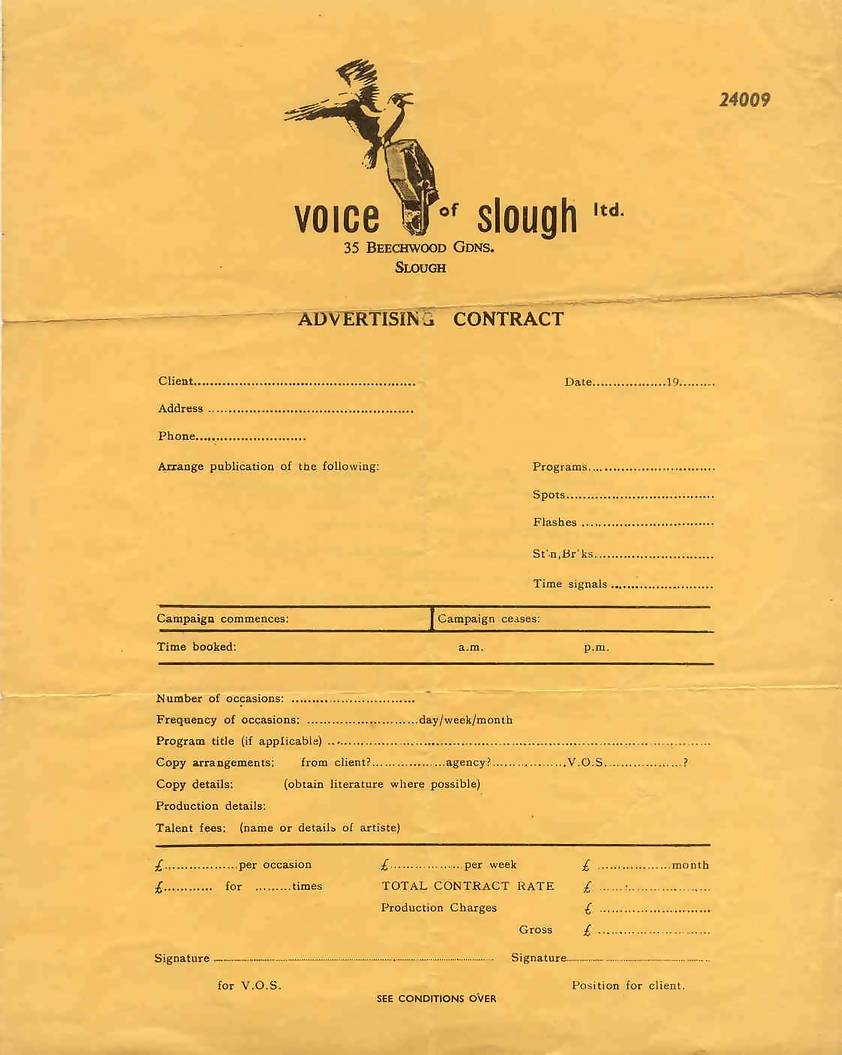

An extremely rare GBLN advertising contract, courtesy of Keith Martin. Click to enlarge.

|

To begin with, a little personal background. Even as a tiny tot I used to pass the time, not playing the piano as my parents wished, but twiddling with the radio knobs of a big

Cossor Radio with its large station window full of foreign place names, my escape to a wider world out there. No stamp collecting or train spotting for me, I was for the big time trying, indeed striving, to hear all

those stations listed on that radio window on the world: Lahti, Kalenbourg, Luxembourg, Budapest, Rome, Munich. Even Leningrad was listed, probably only because there was room on the dial, not because it could be heard.

Eventually when it could be, Leningrad caused an audible whistle during the 1950s when Radio Luxembourg was broadcasting its English programmes on long wave and it was then that I first heard the correct technical word

‘heterodyne’. Many years later that word did the rounds again as Radio Caroline whistled its very own one-note heterodyne into the dark hours of 1964.

Anyway, returning now to my school days, I was ‘always fiddling about with the radio and listening to all those foreign stations’ as my mother used to shout, then adding ‘turn that off!’ But I

was a naughty boy and continued to listen. For I was the one who could recognise and make foreign radio station announcements in foreign tongues not taught at school: ‘Danmarks Radio Program Twu’,

‘Hilversum aine devaraa’ and there was the big one, ‘Goverick Moskova, chesneja philidachey’. Well that's what it sounded like then and for today's anoraks, still does. Yes, I was the one that

had a window on the wireless world and I learned a lot, so there!

Those were the radio days in the middle of the last century. Perhaps you should be reminded, dear listener, that there were very few record programmes at that time. The BBC was full of house orchestras scraping away with

Musicians Union members doing live performances all over the place. The BBC Third Programme opened at six in the evening; even Radio Luxembourg was broadcasting ‘live’ shows and only a few record programmes.

So, up to the early 70s, many radio stations supported their very own full-time orchestras. Radio Luxembourg had its Symphony Orchestra and made music for English listeners, along with the station's specially recorded

shows with such names as Primo Scala and his Accordion Band, Sons of the Pioneers, Charlie Kunz at the Piano - and there must have been someone playing on his Hammond. These music makers mingled with Platter Party,

Disc Break and Topical Half Hour, with the tag ‘Up to the minute recordings on gramophone records’. For late nights on Radio Luxembourg there was The Voice of Romance with promises,

promises of ‘the glance that follows you down the street, the sun that caresses your face upon waking’. For enlightenment there was The Answers Man with Geoffrey Sumner asking the questions - as long

as they were not controversial and did not ‘violate professional ethics’. Another Radio Luxembourg first - and nothing similar was heard on the BBC until Alan Freeman clashed his cymbals years later for the

Light Programme on a Sunday afternoon - was the show that was a must during my formative anorak radio days. It took place very late at night - the first of its kind for Europe. It was pillow-listening at eleven o'clock

on a Sunday night for The Top Twenty - the top twenty tunes of the week as compiled by the Music Publishers Association of Great Britain, ‘brought to you by the makers of Brunatex and Stayblond shampoos’.

Yes, they were tunes not records. Some years later, a new pop paper, Musical Express (later to become New Musical Express or NME), published a list of records sold in the UK and that became

the format for the revamped programme on Radio Luxembourg. I must add, just for the record, I had to wait until Easter 1965 to do my version of the chart for Radio Caroline.

The Musicians Union Agreement obliged the BBC to limit the amount of commercial records that could be broadcast. It was the so-called ‘needletime’ agreement. There were, of course, the special all-record

shows with deejay star names like Jack Jackson, Sam Costa, Alan Freeman and Desmond Carrington. At other times, in other music shows, records would be incorporated into the programme alongside

the obligatory live bands and orchestras. The record content then would be highlighted in the Radio Times with such phrases as ‘Some Choice LPs and Singles’, ‘A Round of Records’,

‘Sophisticated Sounds on Records’, not forgetting this priceless one: ‘Records of Assorted Speeds, Sizes and Styles to Suit People (PEOPLE?) With Assorted Tastes’. I promise I did not make that

last one up.

|

|

|

|

|

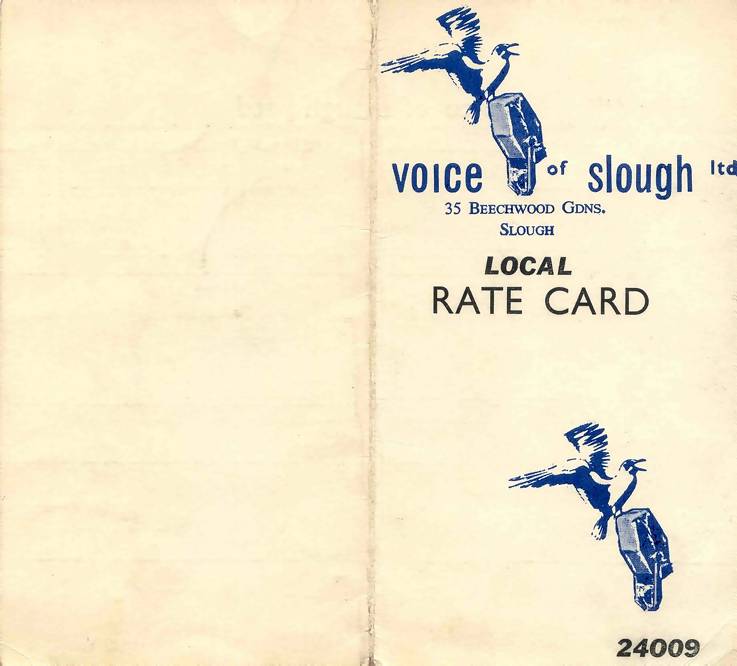

Both sides of a GBLN advertising rate card, courtesy of Keith Martin. Click to enlarge. The Voice of Slough Ltd. was the name of the operating company.

|

I kept my ear to the ground and to the radio, for job opportunities. It could have been as early as the very late 1950s when I heard or read about Radio Mercur broadcasting off the

Danish coast. But I could not engineer a holiday trip, first to Sweden and then Denmark, any sooner than 1960. I have a souvenir Swedish troll to prove the year for, on its wooden base: it says ‘From Lapland,

1960’. I must have had some kind of address as I was already an anorak, perhaps the first, since it was the middle of the last century. I certainly didn't know of anyone else who would ever go to such lengths to find

a radio station with such flimsy information. I won't bore you with the details but I found the place that housed the Radio Mercur studios. As I looked so harmless, like a pleading little lost schoolboy, they let me

into their inner sanctum studio. There they explained that all their programmes were recorded and then transported out to the ship and transmitted on VHF - and all true anoraks know what that means. They did not need a

transmitter mast a mile high. It would have been a stumpy affair because short frequencies do not need a tall aerial array.

Perhaps I should mention that I believe the template for British offshore radio was the short-lived Swedish pirate, Radio Nord. This station was forced to abandon broadcasting off Stockholm in 1962 but its ship, the

mv Bon Jour, later became Radio Atlanta. Following Nord's closure, much bargaining and further sailings to and fro across the Atlantic Ocean and with technical tweaks at Greenore in Ireland plus repairs to the aerial

mast at Falmouth on the south coast of England, the Bon Jour, now called the Mi Amigo after a brief period sailing under the name Magda Maria, was broadcasting Radio Atlanta programmes off the Essex coast. Within weeks

the Mi Amigo was announcing that it was now Radio Caroline South - with yours truly on board ‘your all day music station’.

Perhaps at this point one should note that up to the late 1960s most BBC record shows had rehearsal time with a carefully marked script, a producer with a stop-watch, a knob twiddler plus a putter-oner of records. No

wonder the well known voices of the day would never even entertain the idea of sitting in front of a mixing desk with its faders and PPM meters while having to line-up records from the carefully selected play list.

Those early days in broadcasting were similar to early motoring times, those cars of yesteryear when one had to double de-clutch to achieve gear change, then pull the throttle out to give the engine ‘extra juice’.

Yes, broadcasting way back was not that easy - manual dexterity was more than 50% of doing the job. Nowadays, touch that screen for the music and you're off. Today's deejays have it so easy - but they still can't read

the time!

Leaving the mid to late 50s behind, I was living in London wanting to work in radio and auditioning for Housewives Choice, also for Radio Luxembourg, on the strength of having had broadcasting experience. But I

didn't admit how early, how long ago that was. I was still a schoolboy, 15 years old. It was with the English Service of Radiodiffusion Française - and I still have the 78rpm recording to prove it. Interesting to note,

well I think so, that Radio France, for its English programmes, used their Rouen regional 20KW transmitter sited near Fecamp, the broadcasting base for Radio Normandy in the 1930s. Was it the very same transmitter? It

could have been.

Anyway on the strength of having had broadcasting experience I was allowed to take those auditions, but my desk job with Granada Television continued. I did give a talk about ‘bottles’ on Roundabout

for the BBC Light Programme and I have the five guinea payment slip to prove that too, somewhere.

|

|

|

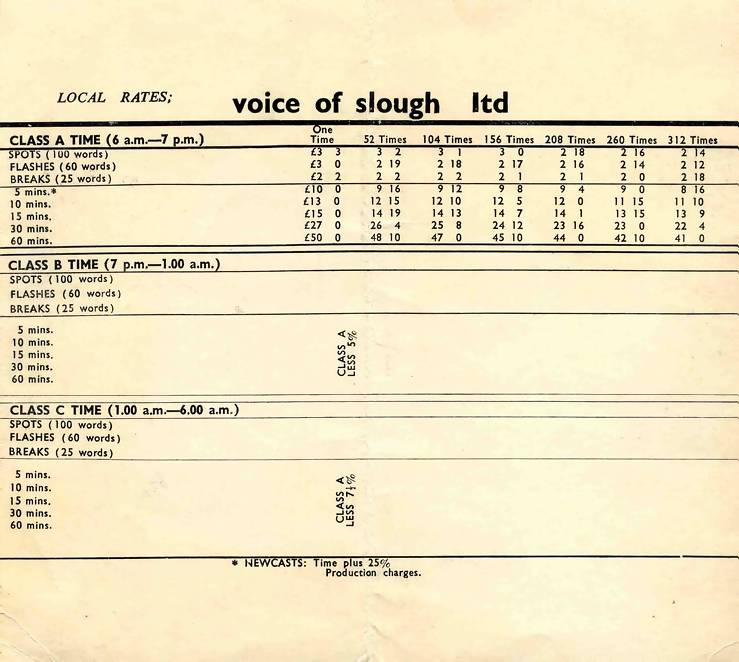

The GBLN studio. Photo courtesy of Keith Martin. Click to enlarge.

|

During my time working for Granada Television in London my pay was around £8 and 10 shillings a week, in cash, plus a daily Luncheon Voucher worth one shilling and sixpence.

Coffee was then only a penny a cup! Would I ever make it to £1000 a year? Later, very much later, when I became a bigger boy, that vast £1000 sum became my daily rate of course!

It was during those early Granada years, when Coronation Street had just begun its long run and Bonanza with Little Joe was top of the TV charts for Monday nights viewing, when my true ambition began to fall

into place. During 1961 I read about a newspaper journalist and his audacious plan to broadcast from a ship ‘from the Nore’ (Thames Estuary, folks!). One has to admit ‘the Nore’ does sound sort of

ethereal as well as having that special something for a secret ship out at sea. I had some research to do.

Eventually I managed to make contact with the man with the radio dream and arrangements were made for us to meet at a café in Slough, Bucks. But how to get to Slough? A Reading ‘B’ bus passed through

Chiswick in West London where I then lived . That bus was to be the link to my adventure into the unknown. That first meeting with John Thompson was at an Eton Road café, a kind of greasy spoon, a Smokey Joe

caff. We just talked and small talked about radio. With all my schoolboy twiddling I felt I was the master craftsman of the radio dial and had something to offer his proposed station Radio GBLN - even if I didn't make

it as a disc-jockey. It was a cautious encounter, that first meeting, a kind of cat and mouse affair. The reason for the feelings of unease was explained later. John Thompson suspected I was an undercover agent for the

GPO, the General Post Office of the United Kingdom, the power then in charge of UK wireless broadcasting. Me, Keith Martin, a spy? Never! An enthusiast or anorak maybe, but never a spy. I was the one who was willing to

give up a secure day job for a leap into the unknown. It soon became clear that if I was an unknowing anorak for years, without doubt John Thompson was a fanatic, obsessed with his true mission to make a radio transmission.

During one of many meetings at his home, just a few yards from the café, I was introduced to John's wife Ellen, who was probably thinking that her husband was pursuing a crazy idea - broadcasting from a ship

indeed! But I was told that it was Ellen who was the reason for the LN being incorporated into the chosen call letters GBLN, so real love and understanding was in the air there. Also, during one of those meetings I

met the man from behind the café counter. He was into this radio venture too. I can't remember his name but he did have a set of Land Rover wheels, the noisy open vehicle vital for the many into-the-late-night-hours

of seeking the location of a suitable ship.

Then there was my introduction to the Thompson recording studio. It was housed in a wooden hut on a council allotment. And who should be there demonstrating his manual dexterity with the mixing desk? It was someone I

recognised from my day job, a Granada post boy, Roger Gomez.

During subsequent daytime office hours we just nodded knowingly, it was our secret. Some years later Roger and I were to meet again, not in Slough, but in Canada. I was a ‘landed immigrant’ as the authorities

labelled me and lucky enough to be working as a graveyard panel operator at CFRB/CKFM Toronto. But I digress, yet again. Where was I?

Yes. With great pride John Thompson explained the workings of his own home-made radio desk. Could I, would I, be able to cope? It was certainly far more complicated than my schoolboy set-up when I played at being a DJ

and insisted that my mother had to stay in bed on a Sunday morning and - LISTEN!

What next was John getting up to? He was planning to build his own transmitter. When I was eventually shown the drawings, it didn't look very big - not much larger than a small fridge and certainly not as vast as the BBC

Droitwich transmitter which I was able to feast my eyes upon whilst on a school camping holidays in the Malvern Hills. During my training period on the John Thompson GBLN console he played a reel-to-reel tape recording

of an American radio station, WKBW Buffalo, the likes of which I'd never heard before - fast talk, tight cues, and jingles. Jingles? Never heard anything like that before, not even on AFN from Germany during my formative

radio years many moons earlier.

For the record I still have that particular WKBW tape, along with another tape of the most fantastic of all radio shows (ahem!) that was never broadcast, but maybe, just maybe, was used to test the Thompson transmitter

from Folkstone. Stay tuned folks, for more of that later.

An extract from that WKBW tape that John Thompson played to Keith, starring Russ ‘The Moose’ Syracuse. The line about “melodies for mothers to make that dish-washing almost nice” must have made

a big impression on Thompson. He used it himself some years later on a test transmission for KING Radio. Recording courtesy of Keith Martin (duration 3 minutes

51 seconds)

An extract from that WKBW tape that John Thompson played to Keith, starring Russ ‘The Moose’ Syracuse. The line about “melodies for mothers to make that dish-washing almost nice” must have made

a big impression on Thompson. He used it himself some years later on a test transmission for KING Radio. Recording courtesy of Keith Martin (duration 3 minutes

51 seconds)

|

|

|

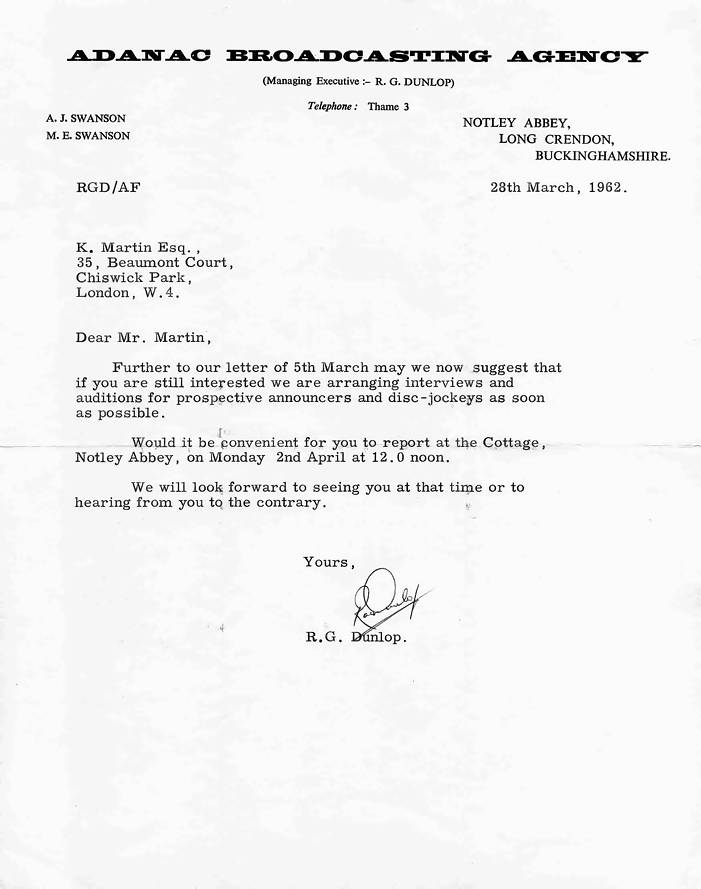

Keith's invitation to audition for GBOK. Click to enlarge.

|

It was during one of many John Thompson strategy meetings that he announced that GBLN had competition - a station called GBOK. There was no shortage of money there, unlike GBLN.

The owner lived at Notley Abbey with the studios in the stables. At this particular summit meeting it was made clear that if anyone wished to join GBOK we were free to do so, but if we did ...! So we all promised never,

ever, to meet the folks who lived at the Abbey. We wanted to stay with John, me in particular, because I had an ‘invested’ interest in the GBLN project: twenty-five pounds of interest, a great deal of money

in the early 1960s and about three weeks of my Granada wage!

So, along with others, I rushed to meet the Abbey boss man at GBOK and be introduced to the programme director, Ray Dunlop who then repeated his name: ‘Ray Dunlop - my friends say I never tire’. Note the

American spelling, as indeed he was from there. Later I was shown the studio complex. Development was taking place in the out-buildings of Notley Abbey and further plans were explained as to how GBOK would sound over a

24-hour programme cycle.

(Web-master's note: Colin Nicol writes “I wonder if Keith's Ray Dunlop might have been Canadian rather than American. I only make the point because the letterhead for GBOK, right, reads ADANAC Broadcasting Agency

and ADANAC is CANADA spelt backwards!!”)

Here my connection with GBLN and GBOK fades a little as time moved on and so did I. GBLN was a very exciting time, not only for me, but for the small band, the original anoraks who developed

the nucleus of what was to become known as pirate radio in 1964.

|

|

|

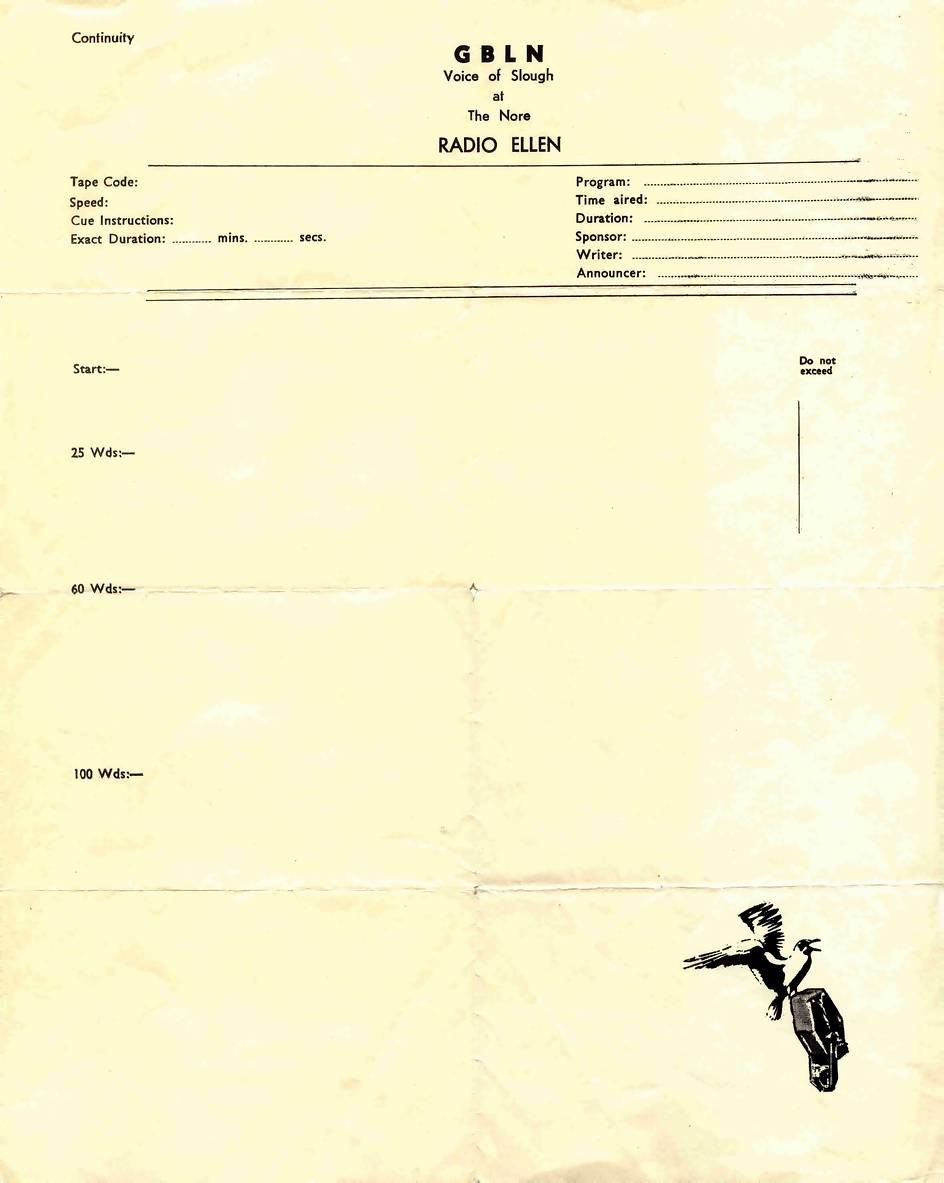

A GBLN continuity sheet, courtesy of Keith Martin. Click to enlarge.

|

There is a footnote. After I faded away from those hectic GBLN days I received a phone call some months later. I immediately recognised the voice, it was John Thompson calling

from Folkestone, Kent. With great excitement he told me he'd built his transmitter and was now broadcasting GBLN. He told me the wavelength and asked me to tune my big Grundig radio, with its aerial straddling the high

chimney pots of my Chiswick flat, and listen out for GBLN as he was ‘on the air’! He might have used those radio shows recorded in Slough by Roger and myself. This was a man obsessed - and he still owes

me £25, my investment in his master plan to take on the broadcasting might of the BBC from a recording studio in a shed! I did try so hard John, I really did, to hear your Folkestone signal but it was not to be,

not on that particular occasion. But the John Thompson saga was to continue and his dream was to come true when he later boarded one of the forts, which I'd told him about many months earlier during our many hectic

journeys into the night to harbours and boatyards and slipways. I'd first seen those gun forts in the Thames estuary on a school steamer trip from Margate to Southend. They were still standing proud, waiting, just waiting

for someone to clamber aboard. Many years later, someone did just that and so other radio stories were about to unfold, including KING Radio with John Thompson (formerly

Invicta, with which he had also been involved) who broadcast from one of the Estuary forts, close to where he always planned to be, the Nore.

I must add it was early in the summer of 2007 that I was alerted to the fact that BBC Essex was going to re-live the days of pirate radio from a ship moored, not in the North Sea - the BBC cheated - but in Harwich Harbour.

With a bit of pushing and shoving and barging, I was invited to make my way to the broadcasting radio ship to perform a self-indulgent three hour record radio show. I arrived early on my appointed sun-lit radio day. I

could not believe what greeted my eyes in Harwich Harbour - a lightship! My memories flashed back 45 years to those hectic days and nights when seeking ships in that open Land Rover with John Thompson. The delightful and

moving end to my GBLN connection was when I climbed aboard the BBC Pirate Radio Lightship. Could this be that same lightship that John Thompson and I had found and inspected and passed as being the vessel that GBLN could

have been broadcasting from all those years earlier? It might have been. It was old enough. Now I find it difficult to forgive myself, that I never announced over Pirate BBC Essex something that would have made John

Thompson very happy: ‘This is GBLN from the Nore’.”

On to the next page.

Back to the disc-jockeys' memorabilia index.

You can read more about GBLN, GBOK and CNBC here.

|