|

The Keith Martin Story

part two

|

|

On this page Keith tells of meeting the people behind CNBC, the Dutch Radio Veronica's attempt to reach an English audience, working for Allan

Crawford, the Australian music publisher who founded Radio Atlanta, the launch of the rival Radio Caroline and, following the merger, his time on Radio Caroline South, spying for the boss.

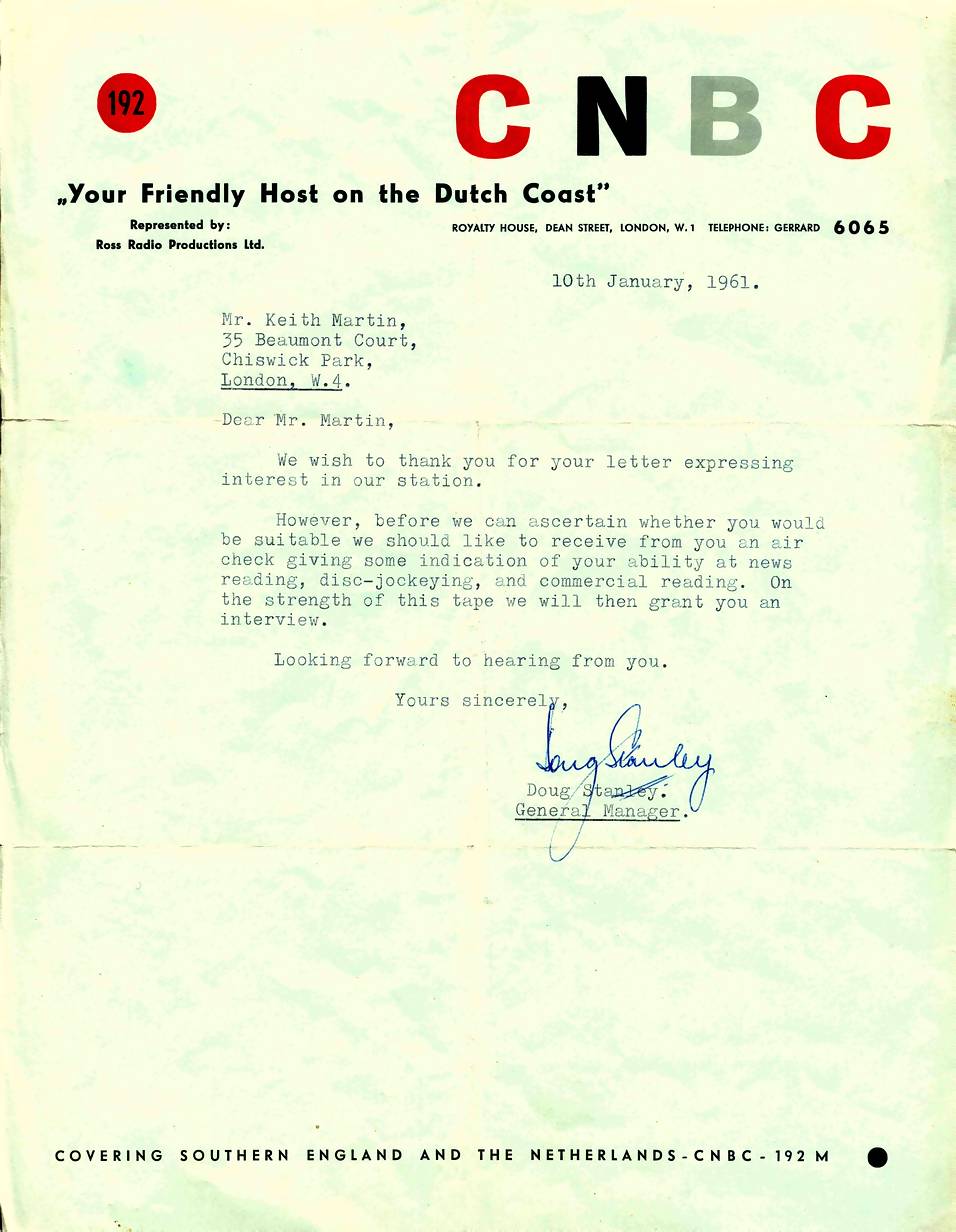

“My association with CNBC also took place during 1961. The Commercial Neutral Broadcasting Company (‘Your friendly host off the Dutch coast’) was set up

initially by Doug Stanley, Paul Hollingdale and others to broadcast English language programmes from 6.00am until noon, before the Dutch ones started,

on Radio Veronica, using the mv Borkum Riff off the coast of Holland. I had first heard Radio Veronica on my specially wavelength-tweaked Sobell radio in my home town of Sandwich. This new station I ‘found’

was broadcasting below 200 metres, the point where most, if not all radios sold in the UK at that time, did not venture - but mine did. As Sandwich is on the Kent coast and radio signals travel much further over water,

Radio Veronica/CNBC was of listening quality along the rest of the east of England coast. However the signal was only just audible in London for an anorak living in a high building - not for the ears of ordinary

listeners.

|

|

|

CNBC's home, Royalty House in London's Soho. Photo kindly provided by Colin Nicol.

|

During CNBC programmes, their Royalty House address in Dean Street London W1 was announced. Need I mention I was knocking at their door within the space of a commercial

break, where I was to pester on-air deejays Paul and Doug. Their plans were to eventually tape the programmes at a studio in Royalty House (at the time they were recording in Holland), then transport the tapes to the

ship moored off Scheveningen. But the signal was far too weak for British listening. After a few months the English programming came to an end with Dutch programmes filling the vacated time.

I'm sure their first transmitter was a hand-built job and either Paul or Doug told me there was little hope of an increase in power - all to do with the electricity generator on board which is a very important part

of generating signal power. And then there's the weight of the generator, extra fuel, more than usually frequent tender visits to replenish fuel for the larger oil tanks needed. So it was never going to be easy

to increase transmitter power.

Few, if any stories, have mentioned electric generators. My understanding is that it takes considerably more than a 10kW generator to fire up a 10kW transmitter. The very high frequency / low wavelength of 192 was

chosen because the small Veronica ship would not cope with a higher mast. So the size of the ship and the small generator dictated the transmitter output.

|

|

|

A letter from CNBC, “your friendly host on the Dutch coast”, kindly provided by Keith Martin. Click to magnify.

|

Just down the road from Royalty House, in Dean Street, were the music empire headquarters of Allan Crawford, whose big hit record at the time was Wheels. What's the

connection did I hear someone cry? Well, Allan had plans with the folks at CNBC to make music together. How CNBC became involved with Crawford was probably to do with their playing his copy-cat records, his cover

versions of hits. Allan's singers and arrangers imitated the original sound of six future hit pop songs, as cleverly predicted by Crawford, and they were released on one 7” disc and sold for the price of

a single 45 rpm record, a real bargain. But he couldn't get BBC air-play for them. Although CNBC did close down in early 1961, I believe it was the station that was the catalyst that brought about Radio Atlanta.

It should be remembered that up to when Radio One first began in 1967 and for some years after, the popular groups of the day, including the Beatles, recorded many of their songs again in BBC studios as sessions for

broadcast. Their commercial records could not be played because of the needle-time limit in the way. There was no ‘All Day Music Station’ until Radio Caroline. The BBC had all those restrictions that

ensured that the Musicians Union remained strong and almost dictated how the BBC should sound. Cover versions were accepted as the norm. Many British singers covered popular American songs, just as Crawford was doing

with his six for the price of one. For instance Dusty Springfield's cover of Wishin' and Hopin' had the same arrangement as the original Dionne Warwick hit, and there were many others. Few UK listeners had the

opportunity to hear the original US versions until Radio Caroline played them. Understandably, the BBC favoured the British versions.

I must add, whilst I was on board Radio Caroline, we were told that we must play a certain number of those Crawford copy-cat records every hour and so they were added to the playlist. When I was in charge of the mixing

for a certain DJ, he came to my desk and began rummaging though the records, placing a number into a separate pile, picked them up, opened the port-hole and threw them out into the waters of the deep brown sea! I

protested at this throwing-out! If someone should be deep-sea diving three miles off Frinton, Essex, they might stumble over a certain hand-picked pile of 45s. With today's DNA technology it should be possible to

prove that it was Simon Dee who had a hand in that 40 year-old drop! It is true that when Crawford was in control of the Caroline South ship I was his mole, his seasick agent on board. When

I made it to dry land Allan asked what had happened to the records that should have been played, I told him. Simon was ordered off the ship and sent away for a while. It was only when I had to depart life on the ocean

wave in November because I was so ill, did he return.

But I am getting ahead of myself. The accumulated paper work from CNBC was deposited with Crawford in the hope that the transmitter power of Radio Veronica would one day increase and CNBC would be re-launched - but that

was not to be and the plans for Atlanta were revealed some two years later.

|

|

|

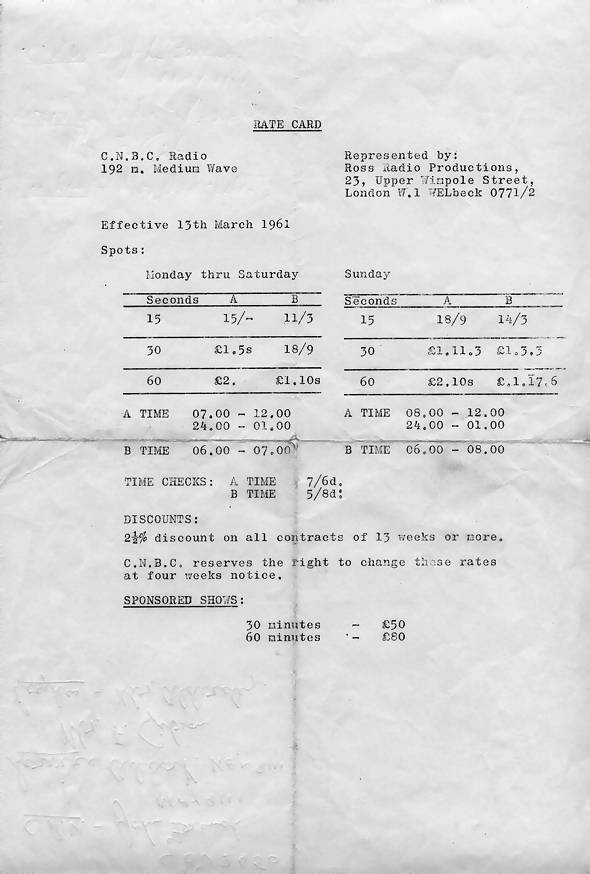

CNBC ratecard, kindly provided by Keith Martin. Click to magnify.

|

During the embryonic months between the close-down of CNBC and the emergence of Project Atlanta, I answered an advertisement for a ‘Representative for a radio sales

office’. During my interview with Lesley Knight Associates in Hertford Street, just a few doors up from number 38, the home of Radio Luxembourg, I mentioned my recent connection with CNBC. It was then that I was

informed that broadcasting from a ship was not a new idea. During the 1930s a plan had been taken on board to do just that but it had to be scuppered. One of the many reasons must have been not only the brittle

easy-to-break 78rpm records requiring an inexhaustible supply of gramophone needles but there were also the size and weight problems of a large water-cooled transmitter. Perhaps pirate radio broadcasting from the high

seas did have to wait until the invention of the LP and the 45 - not forgetting tape recording, a method used by Radio Luxembourg long before it gained the trust of BBC engineers. But that's yet another story, perhaps

for another time.

I first became aware of Allan Crawford and Project Atlanta when it was mentioned in the gossip column of a Fleet Street newspaper during the summer of 1963. I believe it was in the Daily Express William Hickey

column. How did Allan meet up with (rival Radio Caroline boss) Ronan O'Rahilly, was it at some kind of club? After all, Dean Street is in the heart of Soho and Ronan was involved with the Scene Club in Ham

Yard. But this chance meeting, no matter where, no matter how, was going to be the bugbear that was to prey on Crawford's mind time and time again. It was Ronan's plan that brought about both ships being docked at the same

shipyard in Ireland. The Radio Caroline ship Fredericia was the second in port so blocked the exit to the high sea for the Crawford crew on the Mi Amigo. So, that was one reason why Ronan got on air first, but there

was another reason which will be made crystal clear later.

It must have been during the period late January/early February '64, when Allan was having doubts about the situation. I can still visualise him in barely suppressed fury as he finally realised what Ronan had been

doing. I can recall him asking me what did I know about Leslie Parrish, who was about to be appointed Sales Director. I knew him through my Granada years. He was an account exec, as they were called, and Arthur

Pelteret had been taken on too. What did I know about them both? At this time, Atlanta's running costs were escalating with no revenue coming in. Crawford had taken these expensive folk on board, including another -

Alan Phillips also from Granada. Their office was at the very top of the Dean Street building, a room with large panels hanging from a post in the centre where all the commercial spots were to be marked. These

were vast sales display boards, one side for each month all marked-up into days, that kind of thing. Anyway he was thinking that he'd taken this expensive group on far too early and there were no spots being sold -

and how could there have been? Who would know about the project? Things were secret, well kind of, and who in their right mind would book a spot on an unknown? Everyone would be waiting to hear something on air first.

Ross Radio Productions (later to produce sponsored shows like Call In At Curry's for various offshore stations), had been selling air-time for CNBC earlier - or, at least, trying to. It was difficult because

nothing was heard of that station in London - only in Sandwich! I've no idea how much everyone was being paid. I wasn't on the staff yet. I was still being TV-paid but there was an understanding that he'd call on me

to give up the day job and work for Atlanta when the time was right. Crawford did not know about selling air time and questioned what they were doing. So I enlightened him.

|

|

|

One of Allan Crawford's cover versions. Scan courtesy of Colin Nicol. Click to magnify.

|

This was also the first time I'd heard about the two full-time song-smiths on Crawford's Merit Music payroll, Alan Zeffertt and Tony Day. Both went out to the ship much later

(as disc-jockeys Mike Allen and Eddie Anthony). Alan could certainly talk on air, he knew the music. Crawford had gathered about him cautious men. He was particular,

though not always well-judged, in his choice of friends and whom he trusted. He kept his private life to himself but there was one female in his inner circle who was a close confidante and friend, someone who proved to be

a spunky lady: the redoubtable Kitty Black. I believe at times her enthusiasm for the radio project had to be suppressed. She was feisty, despite appearances, and from a well-to-do South African family. Inexplicably, Allan had

ignored good advice from her and his other closest colleagues about the growing threat from the newcomers from dim-lit clubs.

But I digress. This is not a name check-list of all those involved. I am following a complicated meandering journey, a story that must be told for the record. I can only recount it as I recollect it happened and not

hypothesise.

During my many visits to the Merit Music empire in Dean Street I was invited into the inner sanctum of British pirate radio, the studio where sat John Junkin recording programmes for

Radio Caroline. What was all that about? Why was it being done there at Project Atlanta? But I was only a ‘visiting fireman’ from Granada Television, an anorak with privileges, who felt he should not ask

too many questions, just observe.

Upon reflection and with a dash of hindsight, why did Allan Crawford allow the Ronan intruders to record radio programmes on Project Atlanta equipment in his Dean Street headquarters? Were there announcements on

those tapes that said, ‘This is Radio Caroline’? Before long I became a Crawford confidant, one of few maybe, and he alerted me to the situation regarding his conniving Caroline competitor. I was at home

in Sandwich on the Kent coast on that Easter Saturday of 1964. Like a truly committed anorak, I was twiddling with the specially tweaked Sobell radio with its all-hearing aerial strung between the chimney stacks,

when I heard a clear powerful carrier - no music, nothing - just a whooshing noise well below 200 metres. I could hardly contain myself. Was this the wretched radio competitor? At that time, I did not know the name

the station was going to be called. Did Crawford? I phoned Allan at his mansion flat in Victoria and broke the painful whooshing news. Calmly Crawford confirmed ‘That will be them’. I certainly had mixed

emotions, a potent combination of elation and sadness as I listened to a dour voice announcing ‘This is Radio Caroline, your all day music station’. I'm sure it was not a voice belonging to one of the

Caroline cohorts I had heard at the Dean Street studios. But I was soon to be full of forgiveness and bursting with excitement as a few weeks later I too was to be bobbing on a ship where, along with other duties,

I was Simon Dee's panel operator (and at times he was mine too), slipping on the discs and mixing a seamless stream of songs for many a Soundtrack programme.”

|