Ray Clark has interviewed numerous people involved with Radio Caroline for his documentaries and his book, Radio Caroline: The True Story Of The Boat That Rocked (reviewed here).

One of them was Martin Fisher.

Martin joined Caroline in January 1977 as an engineer but was immediately asked to present programmes as well.

He can still be heard on the licensed landbased incarnation of Radio Caroline.

We are grateful to Ray for sharing the conversation with us. He opened the interview by asking Martin about the station's music format at the time he joined.

MARTIN FISHER: Well when I first arrived at the beginning of '77 it was complete free choice. Having said that we were told it was important to have good taste in music and there were some unwritten rules with

Caroline. We were obviously an album station but played things... there was a definite line in the sand where anything that was seen as too commercial, pop commercial music was kind of frowned upon but more serious music we could play.

The way I used to personally tell people at the time was that, for instance, we would play Blondie who were sort of up-and-coming new wave but we wouldn't play Abba. They were just too commercial, too mainstream. It wasn't Caroline.

And I think the listeners appreciated that. We sort of made the decisions for them that this is the kind of cool music you should be listening to. Forget the commercial stuff, other people can do that. And I think that was one of

the great strengths of the station that we chose wisely the music we were presenting.

RAY CLARK: Were there any plug records at the time?

MF: There were. I don't know that I can actually remember which ones. I have a bit of a feeling Motörhead might have been one (laughs) but yes there were plug records.

RC: And they were just played in every programme?

MF: Generally the way it worked was, if there was a plug record, you had an album in the studio and you were expected to play a track from it somewhere during the show. You sort of fitted it in the best you could. If there was an album

that, for some reason or other, didn't really fit Caroline's format, the alternative was often to make an advert (for it) so you could play an ad to promote the album which had a similar effect.

RC: And at this time was it the all-day English service?

MF: When I first arrived it was all-day Caroline on 259. Radio Mi Amigo I think was on 192. For my first six weeks that's the way it was until there was a crew change and (Peter) Chicago came back on

board. That was an amazing period on the ship because we probably had more people on board than ever. I think I counted at one point 13 crew which for the Mi Amigo was a lot. When Chicago came back, I remember the mess room looking

more like a plumbers' merchants or something - great coils of copper pipe and stuff, all the materials he'd brought with him in readiness to change frequency. At that point I was asked to remain on board to assist with the frequency

change and, at that point, I sort of stopped doing the shows I had been doing in order to concentrate on the engineering side. If I remember rightly Samantha (Dubois) arrived back with Chicago and she

took over the slot I'd been doing late at night. The frequency change was quite a major thing. This was when we changed Caroline from 259 onto 319 and it had to be done overnight because all the work we did couldn't affect Radio Mi

Amigo, because that was bringing in the money. The plan was to close down Caroline for a week to enable the work to take place. I can't remember the exact dates, it was early March of '77 and there was a closedown programme on the

final afternoon with a kind of tour round the ship. James Ross had a roving microphone; Mark Lawrence was in the studio anchoring the show and I remember I popped up in

several locations around the ship to be interviewed - the transmitter engineer - to explain what was going on (laughs). Chicago was down in his cabin and didn't want to have any involvement with it (laughs). So yes, they interviewed

me in the transmitter room and again later out on deck as it was getting towards dusk, looking up towards the aerial and stuff. Then finally around six o'clock in the evening 259 fell silent.

A clip from Radio Caroline's last show on 259 metres, 3rd March 1977. Mark Lawrence is presenting, James Ross is wandering around the ship with a microphone. He interviews Martin on a windy roof. This recording was made by Dave Bullock

and shared on www.azanorak.com. Our thanks to Dave and Ray Robinson (duration 3 minutes 31 seconds)

A clip from Radio Caroline's last show on 259 metres, 3rd March 1977. Mark Lawrence is presenting, James Ross is wandering around the ship with a microphone. He interviews Martin on a windy roof. This recording was made by Dave Bullock

and shared on www.azanorak.com. Our thanks to Dave and Ray Robinson (duration 3 minutes 31 seconds)

Later that night, after Radio Mi Amigo had gone off and, no doubt, we'd all had a meal to eat, me and Peter went down into the transmitter room to start reconfiguring everything. Basically, during the following week

we had to not only retune the 10kW transmitter to run on 319 metres but also the major part of it was the matching and diplexing networks. The way the ship worked was that there was one aerial, one aerial tower, being fed from two

separate transmitters on two different frequencies. For this to work it was necessary to have a network of coils and capacitors that were tuned to allow each transmitter to independently transmit into the single mast without affecting

each other. This was, as you can appreciate, quite a piece of engineering - and it was quite heavy engineering with copper coils and big high-voltage capacitors and so on. I don't know if it had been done that many times on a ship

before. I suppose Radio England[1] (might) but whether they did it that way or whether they had two wires going up one mast, I don't know. But it was quite a neat solution and it worked very well. But our

problem was that, as we were moving in a lower frequency direction, although the aerial was a good match for the higher frequencies, it was becoming less so as we moved down the band. It was becoming technically more of a challenge. In

fact it did get hot. The feeder cable got so hot that it became red and did have to be increased in size. It went from being a thin copper wire to being a copper pipe. Anyway, as I say, this work went on night after night, always

getting Radio Mi Amigo on air the next morning, and on, I think it was the 9th of March, dead on the dot, we came back on the new frequency. 319, Radio Caroline.

|

|

|

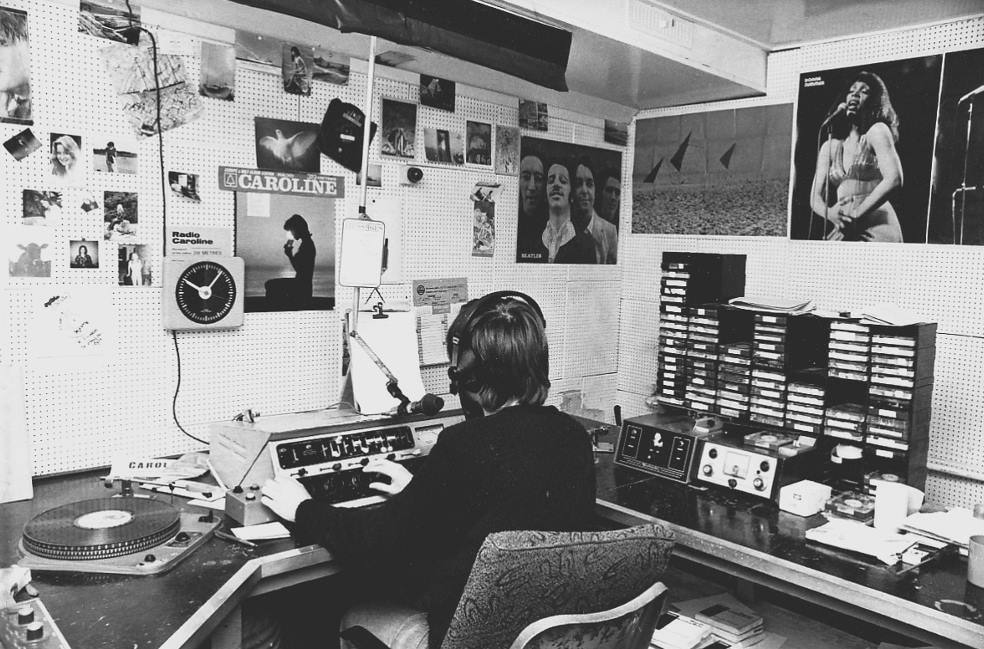

Martin on the air in the Radio Caroline studio. This photo was shared on Facebook by Stevie Gordon.

|

RC: Why was the change needed? Had something else popped up on 259?

MF: What had happened was, I think it was at the end of December '76, before I'd been on the ship, there had already been a move. Caroline was put on 259 metres 24 hours a day (with the 10 kilowatt transmitter) and they put Radio Mi

Amigo on 192 (with the 50 kilowatt). This had a fuel-saving advantage. I remember one of the routines when I arrived, in that first month, was every night at 6 o'clock they would change generators.

RC: Same when I was out there - at 6 o'clock.

MF: The reason being that we were able to use a lower power generator to run the ten (kilowatt transmitter) on its own whereas you couldn't run the fifty on it.

RC: Just as an aside, what sort of tonnage of fuel were you using a day? Can you remember?

MF: I think, with everything running, it was around a ton a day, around a thousand litres, getting on that way.

RC: Just imagine if she was still running now what sort of price even red diesel[2] costs.

MF: Yes, I think it is something that's become very much more expensive over the years. It's probably less viable now than it was then.

Martin Fisher from a morning show towards the end of Caroline's daytime service in November 1977. From 1st December Caroline reverted to night time broadcasts only. Recording shared online by J.E Patrick. Our thanks to him

(duration 4 minutes 30 seconds)

Martin Fisher from a morning show towards the end of Caroline's daytime service in November 1977. From 1st December Caroline reverted to night time broadcasts only. Recording shared online by J.E Patrick. Our thanks to him

(duration 4 minutes 30 seconds)

RC: Can you tell me about any really, really, really rough seas?

MF: I was just thinking back to after we'd had a period of really quite calm weather and you sort of get used to the fact that it's fairly calm, and we'd had supplies out not long before that including - some of the guys were really

keen on mustard and had been asking for mustard and we'd got this massive catering-size jar of Colman's Mustard. It must have been at least a gallon size sitting on the cabinet in the galley. Anyway we were relaxing one evening,

watching the TV in the mess room. As I say, it had been really pretty calm for a while. We weren't expecting the weather to change particularly then all of a sudden the ship just sort of lurched and listed over at an alarming angle as

a wave hit us and all hell let loose. Suddenly we were in this storm and were rocking all over the place (laughs) and we heard this almighty smash bang in the galley. Before that all the chairs in the mess room slid down one side and

we all fell on top of each other in a heap as the ship lurched to one side. At the same time there was this smack bang in the galley. We staggered through into the galley to find it awash with water and broken crockery and (the

contents of) that huge jar of mustard was just sliding down the wall. It had smashed smack onto the side when the wave had hits us (laughs).

RC: Were you ever worried when you were out there?

MF: Well there were times... I remember a really bad night. It had been forecast that it was going to be bad and we were listening to the Shipping Forecast. I can remember being up on the bridge. It was so rough that as the ship

pitched up and down there were times when it actually moved so quickly that the floor went away (beneath you) that you were almost left standing there (laughs). It was pretty scary and to watch the mast waving from side to side, you

prayed that it was going to come back up again because it went so far over one way and you're waiting for it to correct itself and come back the other way. But, as I say, this night with the Shipping Forecast we were all listening to

the forecast as they moved down the North Sea: Dogger, Fisher, German Bight - force 10 and so on. And as they moved down towards Thames and Dover it was getting more all the time. It was getting up to 12 and 13 and we thought “oh

my God”. We were actually saying, to start with, “that's bad. They've got it bad up north”, not realising that it was going to be even worse down where we were (laughs). Yes, absolutely horrendous and I think that was

the night that took out a number of piers around the coast. Herne Bay Pier got split in two that night[3] . It was rough and I think they were worried about us on shore but as always the good old Mi Amigo

came through it. And you felt safe - even though perhaps you shouldn't have done (laughs).

RC: What was the procedure if you found a leak?

MF: I didn't personally do it but I know those that did (laughs). The procedure basically was to create a box section around the weak plate, bang a peg into the hole - you almost made the hole bigger before you fixed it. You needed to

stop the water coming in so the cement could set. Then a patch of concrete would be laid in a block around where the hole was.

RC: You'd find a trickle, a thin plate and you'd make it bigger or just knock the wood through to make it bigger to fill the hole?

MF: Knock a peg into the hole to stop the water coming in and then cement over the top.

RC: Presumably when she went onto the sandbank (in March 1980) she bumped up and down, which popped the pegs.

MF: Absolutely. I think the (hull beneath the) engine room was probably quite thin anyway, an area that hadn't been concreted. A lot of the hull was of course already solidly concreted because of the counter-weight for the mast so it

was only really the areas that weren't concreted out originally that were weak spots.

NOTES

|

|

In 1966 Radio England shared its ship with Britain Radio. The two stations broadcast simultaneously 24 hours a day. It is thought that they did not in fact use a diplexer. They had two separate aerials,

one slung between the two masts and one run up the main mast.

|

|

|

Red diesel is fuel that hasn't been taxed because it isn't intended for use in a road vehicle. A dye is added to show that tax hasn't been paid.

|

|

|

11th January 1978.

|

Back to Ray's chat with Johnny Jason.

Ray's conversation with Robbie Dale is over the page.

|