Colin Nicol: You were shipping quite a lot of water down below. Most of the plates had been fractured, hadn't they?

|

|

|

The Mi Amigo in Zaandam harbour. Photo by Rob Olthof. More of his pictures here.

|

Patrick Starling: Because it was a plate boat, there was hot rivets holding the plates together. The boat had been made, the keel had been made in Kiel, something like 40 years before.

At some point, in the middle of its life, it had been cut in half and they'd put an extra 25 foot of boat or ship in the middle of it and put on the cabin superstructure. Anyway, we started off towards Holland, somewhere around

about 20 knots. It was quite amazing to see ... but gradually, during the night, we dropped the speed down until, I think it was about 10 o'clock the next morning, we were doing about one and a half knots because of the speed of

the water against the rivets, they were tearing the rivets out, so we were now having to pump out more and more water. And they had two pumps on board, each capable of moving something like 120 tonnes of water a minute I think

it is.

CN: 120 gallons of water.

PS: Yes. And they had both of these going full blast, plus electric submersible pumps, which they were using to try to pump the water out. It was very, very late the following evening .... it had taken us 24

hours to cross the North Sea. We arrived in IJmuiden, where the Dutch press were there to greet us.

CN: Where was this?

PS: IJmuiden.

CN: Where is that?

PS: It is at the mouth of the North Sea Canal. It is the home of Wijsmullers, who owned the offshore tender and supply company, and also the Wijsmuller tugboat company. We tied up alongside, and there was

all these press people, photographers from the Dutch press taking pictures of us on the boat. We cleared, oh no, we didn't clear customs. The ship was cleared in to Holland and at about seven o'clock we were towed down the North

Sea Canal to a place called Zaandam, where the dockyard put their pumps on board, they had larger ones, and they started pumping out the bilges. The next day, we were taken in to dry dock. Manoeuvring the boat in to the dry dock

was quite an operation, little tugboats pushing here, there and everywhere, and shunting us in. It was quite nice to watch. Anyway, that whole operation was done.

CN: How long in Holland altogether?

PS: What happened that week was that they lifted the mast off the boat. It was impossible to do any work on the Mi Amigo because the crane could not get past the mast without swinging around in the opposite

direction, so, to ease that operation, they took the mast off which took something like four to five hours. They drained the dock which it was in, and I can remember they only had, well, the crane was about 80 foot high above

the dry dock, 80 to 90 feet, and the mast was 150 foot high. The whole operation of trying to do that ... they had to re-rig the crane to get the right leverage to lift the mast off. It was quite an interesting engineering

operation. During this time, I was living on board the boat; the chief engineer was living on board the boat, and also they left a steward on board the boat to look after us and cook for us. Because of the transmitting equipment

and also the records there could have been a lot of pilfering going on, so they thought it best that somebody stayed on board to guard the boat. As we were in dry dock, we had to use facilities on shore for washing and eating.

It became difficult to use the galley on the boat so they sent the steward home and we used the dock canteen. Work on the boat started at something like six o'clock in the morning and went through until about seven o'clock at

night so we had to get up early because there was all the hammering and banging going on. We then decided, or the Dutch authorities insisted, that the transmitters were taken off the Mi Amigo, so in fact we had to disassemble the

transmitters and lift them out of the hull. So these were taken out and they were put in storage.

CN: I think at that stage the transmitters were shipped across to the Cheeta, weren't they?

PS: Oh, that's right. The Cheeta II came on the scene and they needed a transmitter on the Cheeta, so what they did, they took a transmitter off the Mi Amigo and left one on board. So that was shipped to

IJmuiden and taken out to the Cheeta. I don't know how it got on the Cheeta. It was put on the boat there somehow.

CN: Yes, but one was left on board the Mi Amigo?

PS: One was left on board the Mi Amigo.

CN: So how long was the ship in dry dock for?

PS: A month or two? If you hold on, I can give you exact dates.

CN: So did you sail back with the ship once you came back into operation?

PS: Well, I came off the boat and due to some political manoeuvring and everything else, we got a new chief engineer. His name was Paul Dale. And I was sent off. I flew back

from Holland and did, I should think about it, two stints on the North boat. And then I was back in Caroline House and Paul Dale wanted a transmitter, and also some capacitors for some reason, which were in Caroline House, and

somebody had to take them over to the Mi Amigo. And what I didn't know at the time was it was illegal to carry or to import transmitters into Holland. But I had all these components and things. Anyway, I had a return trip to

the Mi Amigo, and I was to go meet Paul Dale. So I bought myself an air ticket after collecting all the parts from Caroline House. I went and jumped on the plane, got into Schiphol. I had a one-way ticket because I knew that I

was going to be coming back on the boat. In fact, I (intentionally only) bought a one-way ticket because I wanted to come back on the boat. I didn't want to fly back and I knew that if I had a return ticket, then I would (have to)

fly back. I wouldn't get my trip back on the boat. I carried the transmitter bits and pieces through and I was going through immigration, and immigration said “you only have a one-way ticket. You don't have a return ticket.

Who is paying for your stay in Holland?” And I said, “well, I work for Radio Caroline. I'm going out to Zaandam to the boat, and I'm going to be living on the boat”. And they said “we don't believe you”.

And I was ushered into the Head of Immigration in Schiphol Airport, and sat down and interrogated. And they said “have you got any proof? Where's your letter of assignment?” And I said “well, I have been phoned

up to catch this plane to get out to Zaandam and to the Mi Amigo”. And they said “well, we can't let you in”. You know, they said “we're going to deport you on the next flight”. I was talking to

some of the other immigration people, because they were all standing around, and luckily one of the customs officers lived in Zaandam and he said “yes, the Mi Amigo is in Zaandam, and I have seen in the paper that she's due

to leave”. And they said “OK, we believe you, but we will contact the immigration people in Zaandam”. Anyway they let me go and I can remember coming out of the immigration office and opened my bag. I realised

I had some Caroline stickers, car stickers and I said “here, have some of these” and I threw about 25, 30 Caroline car stickers on the immigration officer's desk and walked out, picked up my cases as I went through

customs, got into a taxi, and then headed off for the ZSM shipyard in Zaandam where I met Paul Dale. The boat at this time was virtually back into shape. They'd put new boat keels on, they'd repainted the whole of the ship,

they'd put new generators on board, they'd improved facilities for the running of the ship tremendously. One of the things they decided to do was to put a 50 kilowatt transmitter on board. Also, because the mast was off the

boat, Paul had decided that he was going to put a different antenna on it, which was a dipole, which consisted of the mast and in the middle of the mast was an insulator, on which there was a coil to match the mast to the

frequency we were transmitting on.

CN: How does this differ from the other mast that was originally there? I thought the original was a folded dipole.

PS: It was a folded dipole, where you send a signal up one end, and the other end of it is earthed, and this is supposed to be reflected in the sea below the ship.

CN: And the new system was what?

PS: The old system was directional. It had a broadcast pattern which was sort of like a figure of eight, whereas the new one, being a single pole straight up from the boat, it should radiate in all directions

equally. So you would get better coverage. But because of the all-round coverage, you needed a little bit more power to get your ground coverage. So they decided to put in a 50 kilowatt transmitter, which was flown in from

Continental Electronics in Galveston. I think it was Galveston. Continental Electronics. And they were producing this air-cooled transmitter, which was modulated. Anyway, they wouldn't allow us to sail out of Holland with the

transmitter on board. So, after putting the mast on and getting the Mi Amigo back into seaworthy condition, and repairing the plates on the bottom, there was an incident where the shipyard set part of the stateroom on fire. They

had to make good that.

CN: Accidentally?

PS: Accidentally, with a welding torch. Because the way that the boat was, we had a lot of insulation around the hull and somebody had put a torch through the hull and set alight to the

insulation material. Anyway, we sailed off from the ZSM shipyard, down the North Sea.

CN: What's the name of the shipyard?

PS: ZSM. It stands for something: Zaandam Shipping Marine or something. We went through IJmuiden, where we took on a pilot who escorted us outside the three mile limit. Oh (remembering) we waited overnight

in IJmuiden so that the crew could see their families before they sailed out. They had final things, briefings with Wijsmuller, and the next day, which was a beautiful, calm day, we sailed off, and it was about four miles off the

Dutch coast, when the Offshore I came up with three large crates which contained the parts of the new transmitter. Under Dutch law, we couldn't leave with the transmitter, so what they had decided to do was to sail the transmitter

in its packing cases. I gather the Offshore I had said that she was sailing out for some other destination. And she pulled up alongside the Mi Amigo. On the deck of the Mi Amigo had been constructed a derrick. The thing is, to get

the big components down into the hold in the bow of the boat, we had to have a derrick to drop them into the hatch. What happened was the Offshore I lifted the first box on board the Mi Amigo's deck. We then had to break open the

packing case. We then manhandled the cabinet, which was something like six foot six high, about four foot wide and about four foot deep, up the deck, so it was underneath the derrick. We then lifted it up and dropped it into the

hold, and then we had to manoeuvre it out of the way in the hold into the corners, so we could get the other two cabinets in. In the course of doing this, the Offshore I rolled and nearly dropped one of the cases into the sea but

luckily we didn't lose it, and we got it on board and we got all the transmitter cabinets down into the hold safely.

CN: So you fitted that up while you returned to the usual mooring?

PS: Right.

CN: What was the switch-on date, do you remember?

PS: No, I can't remember. Anyway, we got all the parts and everything together, and it was something like seven o'clock in the evening before we'd finished the operation and the Offshore I left us. Paul and

I then sat down and we had dinner and we decided that we were going to assemble the transmitter so that, when we arrived over on the other side - we knew the trip over was going to take something like 16 hours, 16, 17 hours - we'd

have a working transmitter. So that night we worked through and we assembled and got the new transmitter working in 15 hours flat, with the two of us putting bits and pieces in, reading the instructions on how to assemble the

operation. We got the crew to put bracing brackets in to hold the transmitter steady because, of course, something in the hold of the ship would have to be bolted down. So we had arranged and got brackets across the beam of the

boat to bolt the cabinets to. We took the eyes out and bolted them down through the eye holes. This had been fabricated in the shipyard. That night we set off across the North Sea, and in the breaks between assembling, with the

usual Dutch cups of coffee, I can remember going up to the bow and looking over the bow of the boat and seeing this amazing phosphorescence coming up from the bow of the boat, absolutely brilliant white, as the waves broke. And

the next morning, after working all night, we sailed around the, what's the name of the ... the Roughs Tower, we passed the Roughs Tower, we sailed past Radio London, we sailed past the Cheeta that was broadcasting. And we listened

to the Cheeta. I remember them saying the Mi Amigo had arrived back. And we then took up station south of the Cheeta. That day we progressed and started doing tests, and of course everybody wanted to get back on board, so people

were ferried about. And we worked on tuning the transmitter into the aerial system. At the same time, because they'd rebuilt the radio studio, that work had to be put together and finished off because when I arrived on board, there

was no mixing desk or anything else connected up. And this took about three weeks after we got back.

CN: At this time, the two ships were in sight of one another?

PS: Oh, the ships were in sight of one another.

CN: And the Cheeta was broadcasting, and the Caroline was ...

PS: The Caroline was making ready to go back on. Also, they laid down new anchors for us, of which they did ...

CN: Was it the same system as before?

|

|

|

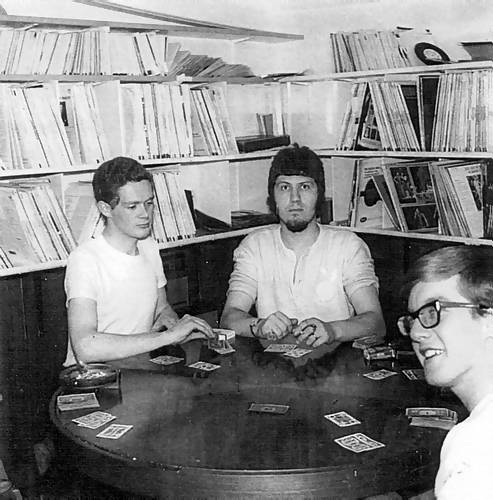

A game of cards on the Mi Amigo. Left to right: Patrick, Dave Lee Travis, Mike Ahern. Photo by Carl Thomson, provided by Colin Nicol.

|

PS: No, they changed the system. Basically, it was the same system, which was what they call a crow's foot anchor, where there were three anchors that go out at about 120 degrees from each other. And then

from a central point of the three anchors, you get a chain coming up to the bow of the boat. What had happened the first time, and why the anchor chain broke, was because the anchor chain came straight up from the seabed. There

was a swivel which allowed the chain to turn at the meeting point of the crow's foot, like the centre of the star. And that chain came straight up over the bow of the Mi Amigo, and was then tied around the capstan balance. The

new system was similar to that, but what they did was to put a swivel at the top so just over the bow of the Mi Amigo, there was an additional swivel which had to be kept greased. The reason why the anchor chain broke in the

first place was the Mi Amigo used to swing around the anchor chain on the tide. And of course, you'd go around in a clockwise direction, you might do a couple of turns anti-clockwise, it was never predictable which way the boat

was going to turn, depending on the wind, the tide, in fact the elements. What happened was the swivel at the bottom of the anchor chain, which is underwater, seized up and as the boat had been swinging around, it had kinked the

chain so when the wave that broke the chain snapped, it sheared on one of the kinks. One of the easy ways to break a chain is to pull on a kink and that is what gave way ...

CN: So the new system prevented that happening?

PS: The new system prevented that happening.

CN: How did it swivel on the bow?

PS: Well, the anchor chain came over the bow, and in the length of chain between the bow spread and the water, about two foot below the bow spread there was a swivel link which allowed the boat to turn on

the chain so the chain would not get kinked. And you could always see if the swivel was turning.

(break in the recording)

PS: I can remember on Radio London the cook going berserk. It was after the Mi Amigo came back from ...

CN: You were still on Caroline.

PS: It was just one of the stories we heard. One of the stories I heard was that the cook went berserk one night and the captain on Big L called up the lifeboat with a couple of policemen on board, and the

thing is he had the cook arrested and taken off the boat for trying to attack the steward, I think it was, with a knife. So he was handed over to the arms of the law. The result of this was that the cook we had on the Mi Amigo

was transferred to Radio London, and we ended up with this little steward doing the cooking. And this all happened on a Saturday night. On the Sunday, it was customary to have sort of braised chicken with vegetables, with

nutmeg sprinkled all over them. I think you remember that, don't you? (laughs) Do you remember this incident?

CN: I can't remember.

PS: Sunday lunch came around. We were waiting for Sunday lunch, and of course the little steward had got one of the ABs helping him in the kitchen, in the galley, if I've got it right. And the galley door was

open, and I was on deck, and I saw this pan with a whole load of matter being thrown over the side of the boat. It transpires that this steward didn't know really how to cook at all. He never really took an interest in it. He had

to cook all these chickens. What he had done was he had got this tray of boiling water. He had been down to the stockroom, and got, I think it was half a dozen chickens out of that. He had thrown the chickens into the water in

their polythene bags, frozen, with all the giblets inside in their little polythene bags and he had boiled the chickens and of course when he came to open the polythene bags, the chickens had just fallen apart completely

and realising that he couldn't serve this stuff, all that I witnessed was the mess being thrown over the side of the boat, because he didn't want the captain to know about it - that he had messed up. So he had another go, none

the wiser for this. He boils the chickens and they fall apart, so he proceeds to collect all the meat he can, takes the bones off it and makes this pile of chicken meat. Not knowing how to present this, he makes up this blancmange,

which I think he thought was a curry sauce, and proceeds to put the chicken into the blancmange and lets it set. This was served up on the table, a large inverted bowl-shaped blancmange with chicken in it, of which, because we

were hungry, we thought we had to eat but the thing is, it was really repulsive. Most of the people who got to it were sniffing the stuff but just having the soup, which had been prepared, and, of course, the Dutch bread.

Anyway, ever since that day I've had a sort of allergy to, well, an avoidance of eating chicken.

(break in the recording)

I can remember one day getting on the train. Oh, of course, the usual thing going out to the boat was to buy a cheap day return ticket at Liverpool Street. Get on the eight o'clock train to Parkeston Quay.

You'd get on the boat and give your ticket to one of the disc jockeys coming off, because we all saved money, because we used to get reimbursed for the full train fare. One day I can remember getting on the train and we used to

have breakfast on the train going out. There used to be all these city gents, and there used to be a lot of disc jockeys going out on a Monday morning. This Monday morning it had been arranged for José Feliciano to go out

to the boat, because he wanted to do a sort of live broadcast and he wanted to say that he'd been on the boat. So we were sitting down in the, in the restaurant car, and we were all chatting away and talking about things, and all

these stuffy businessmen going off up to Chelmsford and, and wherever, and José started singing in the restaurant car. José started talking about numbers, about songs and how they went, and he was singing them. And

he's got a whole sing-song going at breakfast, and you can imagine, there's a face on these businessmen with what was going on, you know. It was totally unexpected. They were used to just sitting down and hiding themselves behind

newspapers.

Interview © Colin Nicol.

Back to previous page.

|