RAY CLARK: Back to the amalgamation. Did you have any choice of going north or were you just told you were going north?

ALAN TURNER: Oh no, we had a choice. We could either stay on the Mi Amigo in the south of England or stay with the Caroline and sail north. Tom Lodge, myself and Jerry

Leighton elected to stay on board and it was midnight on that Friday that we up-anchored and set off on our epic voyage.

RC: What did you take? I suppose you had everything. You had the records that Caroline had got. It was the Mi Amigo which was in a bit of a dire state because they hadn't got anything, I guess.

AT: They had some records. When Caroline first started we had hardly any records at all. Full stop. But we stayed on board and at midnight on the Friday we set off. Then the adventure started the following morning because it was about

8 o'clock-ish or so, Tom came bursting into my cabin and woke me up. He said “have a look out of the window, out of the porthole” and I looked out of the porthole. We were just going past Beachy Head at that time and I said

“what am I looking at?” because you couldn't make out details from that distance. He said “have a close look through the binoculars”. So I looked though the binoculars and the top of Beachy Head was packed with

people watching. This must have been somewhere about half past eight in the morning - Saturday morning so lots of people around, nice summer's day - and I went up on the bridge and had another look at it. Then it suddenly occurred to

me that I could signal them with a mirror. This came about because I had been given, some years prior to that, a heliograph. This was standard equipment in all air-sea rescue dinghies that were issued to bomber and fighter pilots so,

if they were downed in the sea, they could signal to rescue aircraft. So I went down to the cabin and over each hand-basin was a quite large mirror. I unscrewed that, off the wall, went back onto the bridge and started flashing the

shore. Bright sunny day, very easy. Some people cottoned on to this very quickly I must admit and started flashing back but they were just isolated flashes from the shore. Miles apart some of them. So then we started broadcasting that

Neddy was going to go up on the bridge and, when you saw the mirror signalling to shore, flash back with your headlights or mirror or whatever you'd got. So I went up a little while later and started flashing the shore. We could see

east to west probably 20, maybe 30, miles distance. I started flashing and of course moving the mirror along the shoreline so that everyone could see it. Well it was magical the first time because it was just as though someone had

flicked a switch on because hundreds of these lights started flashing. And as the day progressed, more and more people cottoned on to this so every time I started flashing, more and more lights appeared. It was just incredible to see

thousands of lights flashing at you. That's when the famous Caroline flashing started. It was about 9 o'clock on that Saturday morning (laughs).

RC: The route must have gone outside the Isle of Wight...

AT:Yes, off St Catherine's Point, right away along the south coast.

RC: Did you stay on the air all the time? Did you do 24 hours?

AT: No, not initially. We did run quite late into the evenings but with only three of us on board it was a bit too much.

RC: So you were up off the Cornish coast I suppose, turn right and head north...

AT: That's when the next interesting episode started because I think it was Tom said on air that it would be nice to see the Sunday papers but there was no chance of us getting them because the skipper wouldn't stop. We didn't know

it at the time but I think there was a garage owner in Cornwall - I have a clipping of the incident that is on The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame (see this page) - anyway somebody came

out in a speedboat. We saw the speedboat coming out from the shore and the skipper said he wouldn't slow down, wouldn't stop for it. He said “if he can catch us up, it's fine” and eventually the speedboat did catch us up

and they threw a selection of Sunday papers on board, for which we were very grateful. Because, bearing in mind we had no contact with anyone on shore at all; no telephone; no radio contact; no nothing - so we knew nothing about what

was going on and there was an enormous number of people watching our progress. So we rounded Land's End and set out across the Irish Sea. We went past the Smalls Lighthouse, which is off the Welsh coast, and then eventually made

landfall at the southern tip of the Isle of Man. We were anticipating a big reception when we got to Ramsey Bay. So we sailed up the east coast of the Isle of Man, past Douglas, sailed into Ramsey Bay... absolutely nothing. Very

picturesque scenery as anybody who has been to the Isle of Man will know, and we picked up the anchorage near the Bahama Bank and sat there. Looked at the shore, still nothing (laughs). Not one single yacht or ship came out to meet us.

The reason for this was that it was Tynwald Day. We didn't know that. And, of course, Tynwald Day is a big public holiday in the Isle of Man. Anyway we'd been at anchor for a couple of hours or so and somebody said “oh there's

a boat coming”. So we all rushed outside and looked. We could just make out this tiny speck on the sea near Ramsey harbour. So we got the binoculars. Had a look through the binoculars and it turned out to be a 2-seat canoe which

slowly made its progress towards us. These two young lads in the canoe said that they'd heard about us coming and just wanted to come out and see what all the fuss was about. And they gave us, funnily enough, a sprig of white heather

for luck. I don't know what happened to that but that's why they turned up.

RC: And the luck continued for Caroline North. When did you realise that you were involved in something huge?

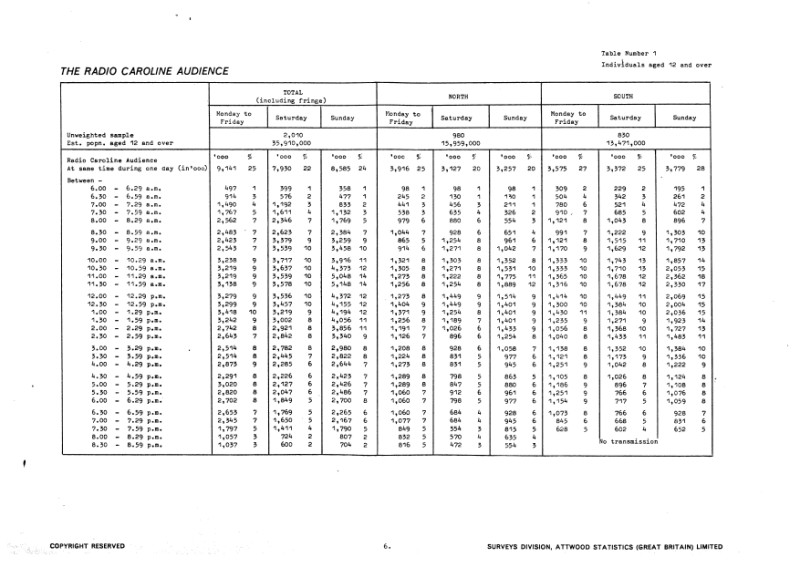

AT: Well it was in, I think, about August time when they had another audience survey carried out. That covered the whole of the UK but not including listeners in the Republic of Ireland. And it was in excess of 24 million people so at

that time that was roughly half the population listening to Caroline. That was because of the combined Caroline coverage from the north and south ships.

|

|

| A page from the audience survey mentioned by Alan. Commissioned from Attwood Statistics Ltd., the research was carried out in August-September 1964. Scan courtesy of Colin Nicol. |

RC: And you'd given up with the tapes when you went to the Isle of Man?

AT: Yes. And then we started getting quite a lot of new people turned up on the ship - DJs and what-have-you.

RC: Can you think of any names?

AT: Yeah. Mike Ahern, Roger Gale - now an MP. Yes, there were quite a few new faces.

RC: I guess you were broadcasting not just to the Isle of Man but you've got Belfast, Liverpool, Manchester...

AT: Yes and also interestingly during the summer months, because of the strange ways that radio waves operate, we started getting reception reports from the east coast of the States and Canada which, when they arrived, we were amazed

that it had travelled that far. Then of course, because we were mentioning the Isle of Man hundreds of times a day - what the weather was like on the Isle of Man, what the sea was doing off the Isle of Man, and all the rest of it - the

benefits that were brought about for the Isle of Man tourist trade were enormous. And when we went ashore at changeover days, the crowds of people in Ramsey were unbelievable, unbelievable numbers of people.

RC: How were you transported from there to home? Flying presumably.

AT: From the Isle of Man back to London always by air. Cambrian Airways - the old Vickers Viscounts. I used to meet quite a lot of people who were appearing in the Isle of Man (on those flights). I met Val Doonican umpteen times,

either coming from or going to the Isle of Man on Cambrian Airways. Various other people that were appearing in the seaside shows at the time.

RC: Can you think of any of the advertisers that you had up north? Presumably you mirrored the national advertisers that the south ship had but also some locals as well?

AT: Yes. There were a lot of advertisers but I can't remember any names off-hand. They ranged from small one-man garages to big chains of retailers in the north of England and Ireland.

RC: And tendering? You had your own tender there obviously.

AT: Yes. We had a fishing boat which was called the Essex Girl. She appears in lots of photographs because obviously when the tender, the Essex Girl, came out she brought photographers, film crews to interview people on board plus,

of course, all the various pop stars which came out to see us.

RC: Can you remember any of those?

AT: Dave Clark was one of them. I'll think of some more in a minute.

RC: Was there any tie-up with commercial television? Did you do anything with (local stations) Granada or Border, or anything like that?

AT: No. I did the only broadcast on the island. I did a ‘Down Your Way’ type travelogue which I've just recently got a copy of. I never kept a copy of it at the time but there were a lot of people who monitored our

broadcasts religiously. Some of the actual written logs of what was going on, and who said what at what time, are amazing when you look back and think of the effort that went into recording every single word that was mentioned on air.

And a lot of people recorded the programmes and shows. I did this... (programme from the Isle of Man). I spent about a week ashore, travelling all round the island to the various interesting places and, after the interview with whoever

I was interviewing, I asked if they wanted a request, and I played the request when I got back on board.

RC: Did you have any contact with London or were you out on your own?

AT: Oh we were very much on our own, yes. In the early days there were no playlists. We started off, Caroline in '64, with a very simple format of male, female, instrumental and we just fed the Top 20, Top 40 into those records. We

played lots of the old classics - Ella Fitzgerald even Glenn Miller, you know you played what you fancied.

RC: And again, do you remember Ronan coming out to the northern ship?

AT: If he did go, I wasn't on board at the time. I can't remember him actually going up to the northern ship. I think he did but I'm not sure.

RC: And then in 1965 things changed and (new director) Philip Solomon turns up. That made quite a difference to you?

AT: It did, yes. There was, at the time, worries about where a lot of the money was going and I think Solomon had introduced some strict financial constraints as to where this money was actually winding up. Lots of quasi rules and

regulations came into being which a lot of the people on board the ship resented. I think resentment is a good word. So moves were afoot for us to start our own ship. Because we could see the pitfalls of where things were going wrong

and we had the expertise and knowledge to get it set up. That's what I was involved with subsequently but it never got off the ground because of the government.

RC: Were there any links with the southern ship?

AT: There were no direct links. We did our own thing and they did their own thing. Of course they had the big challenge of Radio London in the south. We didn't have that although subsequently there were other stations started up in

the north but nowhere of the size and coverage of Caroline. I did go out to the southern ship after the merger. I think I did a little spot with Tony Blackburn while he was on board but that was all. The

two entities were completely separate really.

RC: Did you ever meet up with any of the southern guys other than... I mean did you go to the London office?

AT: That's the only time we would ever meet, in the London office. If I was in London I would always go into Caroline House because I was great friends with Gerry Duncan who ran the studios in London. He

and Carl Conway processed all the commercials. Gerry had had a history of working in the film industry and so I got to meet quite a few people involved in the film industry through him at that time. He

was down in the basement in his own little world, completely detached from the rest of the building (laughs).

RC: It was a huge building wasn't it?

AT: Huge was not the word. It was palatial, that space in Chesterfield Gardens. In fact during one of the reunions in recent years we walked up from Shepherd Market in Mayfair, just to have a look at it for old time's sake. I think it

is now executive office suites or something of that nature. But it was a big, big building. It had a permanent resident on the top floor, a Swedish chap whose name was... It will come to me in a minute. He was nothing to do with

Caroline; he just had a flat on the top floor.

RC: So a lot on money was made?

AT: It was. I think it was at about the time of the merger when the advertising really started to take off big time, really big time, and the amount of commercials that we broadcast was phenomenal, really phenomenal.

RC: I guess every household name was there, cigarette advertising, all the big companies.

AT: Yes, yes. I think there was one famous clip concerning the Egg Marketing Board at one time. I think Tony Blackburn was involved with that. I might not have this story right but I think on air they mentioned, after the expression

“go to work on an egg” came out, they said “what size egg was that?” and somebody said “it's a 500cc one!” (laughs)

RC: Happy days.

AT: They were. A great adventure really. We had no idea, especially those of us who joined it at the start, what it was going to become.

|

|

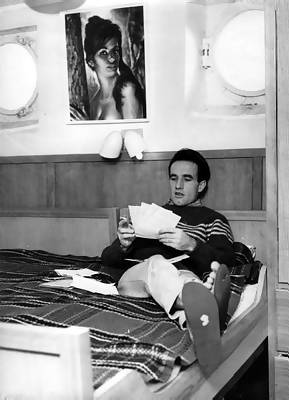

| Alan Turner in his cabin on Caroline. Photo courtesy of Alan. See here for more. |

RC: And seas - we must mention those - you must have had some rough seas, especially up off the Isle of Man.

AT: The winter of 64-65, that was horrendous. One hurricane force gale. We had, I think it was, a 5 ton anchor down and we dragged that nearly four miles, lost the windows out of the bridge and at one stage the skipper got us all,

everybody - the crew and the DJs, radio staff - all in the saloon because he wanted us to be together if we had to leave the ship. It was really, really rough. Frighteningly rough because in the saloon the tables were bolted to the

floor but the chairs weren't and along both sides of the ship, against the walls of the saloon, were long settees because Caroline had been a passenger ferry in its commercial days. And when the ship rolled - and of course this was

accentuated by the weight of the mast carrying the roll-over further - you had no option but to run downhill and then you had to, when you reached the settees on the bottom side as the ship was sitting at that time, you had to jump up

on the settee because all the chairs came hurtling across the floor and if you didn't get up on the settee you got your legs crushed (laughs).

RC: You had a big grand staircase as well didn't you?

AT: Yes. It wasn't palatial but it was quite nicely fitted out. It was typical thirties, you know, where they have the double-sided staircase going down to the cabin accommodation and the next lower deck.

RC: A comfortable ship, a happy ship?

AT: It was large. The cabins were fairly roomy, bearing in mind that they were only ever designed to be used for one or two nights at sea. The cabins weren't bad at all.

|