Ray Clark has interviewed numerous people involved with Radio Caroline for his documentaries and for his book Radio Caroline: The True Story Of The Boat That Rocked (reviewed here).

This conversation with Alan “Neddy” Turner took place in 2014, around the time of the station's fiftieth anniversary.

Alan joined Radio Caroline immediately after the station launch and was on board for the original ship's journey round the coast to the new anchorage off the Isle of Man in July 1964.

We are grateful to Ray for sharing the interview with us.

RAY CLARK: How did you get involved, Alan?

ALAN TURNER: With Caroline? My experience in broadcasting started out in the Far East when I was serving in the RAF. I had got involved in the forces broadcasting units in Singapore, broadcasting to Singapore and Hong Kong. I got

involved in a local station in Singapore quite by chance. I've told this story many times before but I'll relate it again. I was listening to the local station one evening. As the evening wore on, the chap presenting the programme on

the radio said “there's nobody here to replace me in the studio” and he said “if nobody turns up by 9 o'clock I'll finish my programme and shut the station down.” Well I didn't think this was very good so,

knowing where the studios were, I wandered up there and introduced myself. I said “what's the problem?” and he told me the same story that there was nobody there to carry on broadcasting when he left and he said to me

“can you operate any of this equipment?” and I said “well I've never seen any of it before”. He said “have you got a record player?” So I said “yes”. He said “well you know how to

turn the records on and off.” And he said “these tape machines...” which were the big professional Ampex machines... he said “you can understand what ‘stop’ means and ‘start’” so

I said “yes”. “Well” he said “the tapes are all cued up so at 9 o'clock you just press go and that's it.” So at 9 o'clock he disappeared and left me sitting there with this studio equipment which I'd

never seen or handled before but it's a little bit intuitive and, if you understand electrical machinery it's not too difficult to pick up. And that started me off on a good grounding in commercial radio because the forces broadcasting

units were run as commercial stations. So I sold advertising, did all the jobs that have to be done in a radio station, filing records, doing everything from continuity announcements to presenting programmes to making the tea. You have

to have the tea! And then of course, when I came back to the UK in the early sixties, there were a lot of embryonic radio stations all trying to get off the ground because there was a great movement to get commercial radio started in

the UK. I had been for a couple of auditions for various stations that were trying to start but none of which, unfortunately, did get off the ground. My wife Elaine worked in central London and I quite often used to drive through London

and pick her up from work, and we'd drive home together. And this particular day I was parked in the car and I had bought the Evening Standard newspaper, just for something to read while I was waiting. And as I was casually

thumbing through the pages I caught an advert which said “staff wanted for new broadcasting station venture. Apply to the following address.” Well this address was in Fetter Lane in London, and I was parked in Fetter Lane.

I looked out of the car window and there, about two doors up the road, was the number in Fetter Lane to respond to this advert. So, being interested in radio, I wandered in there and it turned out to be the publishing offices of

Queen magazine, a company owned by Jocelyn Stevens. So I walked in and made enquiries about this advertisement. The girl on the reception had no idea what I was talking about so I showed her the

advert. She went off to find out and she came back and said “apparently there are a couple of men in a room on the top floor. I think you'd better go up and talk to them about it”. She knew nothing about it herself. So I

wandered up and found Ronan O'Rahilly, the man behind Caroline, and an old school buddy of his called Chris Moore. We introduced ourselves, sat down and I told them my background.

He said “can you go out on the ship tomorrow?” Well this was on the week - a couple of weeks before Easter. The ship had just arrived off Felixstowe, having been fitted out in Greenore, in Ireland - a port which was owned

by Ronan's father, a very useful place to have. I couldn't go out prior to the station starting on Easter weekend so I went the week after. So I was out there immediately after Easter.

|

|

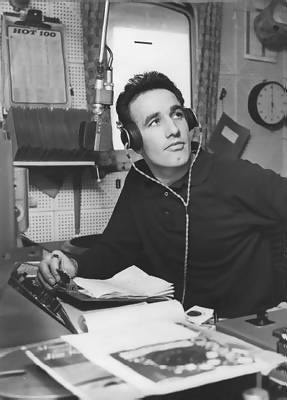

| Alan Turner in the Caroline studio. Photo courtesy of Alan. See here for more. |

RC: On one of the first tenders, I guess...

AT: Yes. In fact I went out on the tender that took Chris Moore back to London. Ronan wasn't on board when it started.

RC: So this would have been, what, the first day or two in April 1964?

AT:Yes.

RC: Who else went out with you, can you remember?

AT: Just me.

RC: And Chris Moore came off?

AT: And then a couple of days later Doug Kerr, a Canadian, turned up. Simon was on board still, Simon Dee, and apart from Ove Sjöström

the engineer - there were two Swedish engineers on board who finalised all the radio and studio equipment - so it was Doug Kerr, myself and Simon.

RC: And tapes. There were a lot of tapes they'd done weren't there?

AT: Yes. Well originally Caroline was designed to be operated purely as a broadcasting unit. There were no plans to have DJs on board as such. All the programmes were going to be produced in studios in London and taken out to the ship

(on tape). So there was the operating unit in the studio and a very small continuity studio because it was not envisaged that anything else other than that was going to be used. But, of course, within weeks of us starting we realised

that this wasn't going to work because sometimes the tender would come out from Harwich with the tapes and simply not be able to get alongside. So that meant that we couldn't broadcast programmes as they were envisaged. We started

using the DJs on board.

RC: Did you have to do an audition or did they just say “because you've got radio experience, out you go”?

AT: That was it basically (laughs).

RC: Presumably as a technical operator - or as an announcer as well?

AT: Well I was going really to handle the management of the studio on board and do the continuity announcements but, as we found out very quickly, that wasn't going to work. Doug Kerr and Simon couldn't operate the panel so I wound up

(doing that and) producing their shows for them. It was just myself and Ove who did most of the panel work in the early days because there was nobody else to do it. And then one or two other studio engineers came on board eventually

and eased the work load but we didn't mind. Originally we were designed to be on board for two weeks on and a week off. That didn't work either (laughs). Sometimes I was on the ship for a month, six weeks at a time.

RC: What about the first response. You must have been there at the time, on one of the first boats out, had you seen any of the response?

AT: No. Nobody in Harwich had any idea what Radio Caroline was. The mere fact that you said it was on a ship anchored off Felixstowe meant nothing to them, you know, because there's lots of ships in Harwich. Felixstowe then was just a

tiny fishing village basically. The only thing that existed at Felixstowe was the remnants of the old seaplane base. All that's there today just didn't exist. So Harwich was the port and, of course, it had been the principle terminal

for going to and from Holland for donkeys' years. We had no communication with the shore. One of the first things the British Government did was to prohibit the use of the ship's radio for ordinary communications. They would process

emergency calls, medical help and the like, but for run-of-the-mill communications they just blocked it. So we had no idea what was going on ashore at all, you know, we were just sat there and played records. We knew the signal was

going out because the oscilloscope told us so - we had an oscilloscope in the studio to ensure that the transmitter was working properly - and it was about, oh, about 3 or 4 weeks after we started broadcasting somebody came out from

head office in London and said to us “I think you'd better sit down. We've got some important news for you.” So we sort of looked at each other and sat down and said “yes, well, what's the important news?” And

they said “you've got almost six million listeners” - and that was verified by ABC, the Audit Bureau of Circulation. This was a little difficult to take on board. We had no idea if anybody was listening to us because we'd

had no response at all. No telephone calls. No nothing. When you think about what could happen today with mobile phones, we would have been inundated with calls and emails and all the rest of it.

RC: Letters must have taken a little while to come through...

AT: Yes they did. On the early tender trips there were very few letters because, although a lot of people were listening to us, they hadn't really got the address buried in their minds as it were. And so it carried on with this

enormous listening audience that we had no idea existed. And of course it carried on like that right up until the amalgamation, shortly after Radio Atlanta started.

RC: I'll get onto that in a moment. Can I ask about the (Caroline) bell? Had that already been decided, that you were going to have the bell?

AT: That I think was an impromptu thing. The first recording of the bell was terrible. It was all wowy and a really poor recording. I said to Ove one day “shall we get this bell re-recorded so that it sounds more like a proper

ship's bell?” So we did that and, to my knowledge, all the sounds of the bell that you hear today are that recording. I don't think it was ever re-recorded afterwards.

RC: And that was on the Fredericia?

AT: Yes. And that's the only thing that exists of that ship today - the bell - which lives on the Isle of Man still.

RC: The bell's still around - and the audio of it as well. Did you hold the microphone or did you ring the bell?

AT: Um. I think I held the microphone. No. It's a bit vague now. It's a long time ago. We took a microphone cable right out across the deck to do it and recorded the audio.

RC: What about the customs boat, the Venturous, which came out? Were you on board then? When the ship came out and asked to see the stores?

AT: No, I wasn't on board when that happened but what did start happening within a few weeks of us starting broadcasting was that a navy minesweeper used to come at least twice a week to check our position to make sure we were outside

the three mile limit, which was the legal limit in those days. And we were anchored actually just off Bawdsey which in itself is a famous site where a lot of the World War II radar experiments were carried out.

RC: Radio Atlanta turned up. Had you got wind of Atlanta coming?

AT: Yes, because (Atlanta's ship) the Mi Amigo was also fitted out in Greenore as well. There were some hold-up with her equipment and I think, if the hold-up had not occurred, she would have been on station first. She took up

anchorage off Frinton about 14 miles south of where Caroline was. We didn't know it at the time but, right from the early days, Ronan had been in discussions about amalgamating the two ships. Then, as you know - I can't remember the

dates... June...

RC: July wasn't it?

AT: July, yes, the tender just turned up on a Friday and announced to everybody on board that the ships had amalgamated and the Mi Amigo was now Radio Caroline South and we were to sail to the Isle of Man and become Radio Caroline

North.

RC: How was that received on board?

AT: We had a big meeting in the saloon and discussed it all. It was agreed that Doug Kerr and Simon Dee would stay in the south and transfer to the Mi Amigo. And Tom Lodge, Jerry Leighton and myself would sail with

the ship to the Isle of Man.

RC: And who passed that on? Did Ronan come out or was it the crew, or Captain?

AT: No. I think it was Chris Moore if I remember rightly. I think the Captain was aware that these things were going on but nobody else was. Nobody had any inclination of what was happening until the tender turned up. It was late in

the evening when Simon Dee and Doug Kerr went on the tender and went off to the Mi Amigo.

RC: The two ships didn't get closer to each other?

AT: No, stayed on station. At about midnight we raised the anchor and set off across the estuary. We went close to - but not very close - to the Mi Amigo. It was pitch black. You couldn't see a thing apart from on the radar.

RC: Can you tell me anything about the tender arrangements?

AT: Yes. We had quite a lot of different tenders in the early days, mostly tugs - either big ocean-going tugs or river tugs which are quite small. There are some photos on The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame

(here) of one of them but I can't remember the name of it off-hand (the Agama). It is one of the tugs we used for quite some time. There was an interesting amusing incident on one of the river tugs which was

called the Hooligan. It was quite small and not suitable for what we wanted to use it for and they dispensed with its services after a time. It was skippered by a really gruff-speaking East End cockney and when it emerged from Landguard

Point at Harwich and got into the open sea, he would call up Caroline on the radio. This really deep-voiced eastender would come on the radio saying (deep croaky voice) “Caroline Caroline Caroline Hooligan Hooligan Hooligan”

(laughs). It was quite amusing actually. I remember they had a young lad on the Hooligan who was obsessed with the speed of this tug and he used this expression which I hadn't come across a lot but is very common in nautical circles

“the speed over the ground” which I always thought was a little bit incongruous as we were afloat on the water and he referred to it constantly as “speed over the ground”. We carried on using tenders that Anglia

Marine, the agents in Harwich, had organised for us.

|

|

| A Caroline tender alongside Parkeston Quay in 1964. In the foreground the tug skipper is talking to shipping agent Don Murrison (right). Photo courtesy of Alan. See

here for more. |

RC: This was the man Murrison wasn't it?

AT: Murrison, yes. It was him. He was really an unsung hero of the early days of Caroline because for the first several months, right up until the time that we amalgamated and sailed off to the Isle of Man, he was basically underwriting

all the costs himself. It was on his word that a lot of the fuel was delivered to the ship - and food. He was saying to the suppliers “don't worry, I'll cover the costs” until some money started coming in from advertising.

There was very little, hardly any advertising in the early months.

RC: Can you remember the first ad?

AT: I can't remember the first ad. I can remember the first main ad was for Bulova watches because they provided a quartz clock for the studio and we used a Bulova time check constantly for a long time. That was one of the

first main adverts. Oh, DON Murrison, that's his name. I suddenly remembered. He had this company called Anglia Marine which I think was in Church Street in Harwich, which is now a private house, and he was instrumental in holding the

thing together in the early days.

RC: They were taking care of all the tendering while the Fredericia was off the Suffolk coast?

AT: Yes. Another big problem we had when we came ashore was with Customs. The Customs people hadn't really taken on board what Caroline was all about and where it was. They were really hot on us, wanting to know where we had got all

these cigarettes from - because cigarettes on board were very cheap. Everybody smoked in those days, back in the sixties. I myself used to get through, when I was broadcasting - because of all the nervous energy that you wind up when

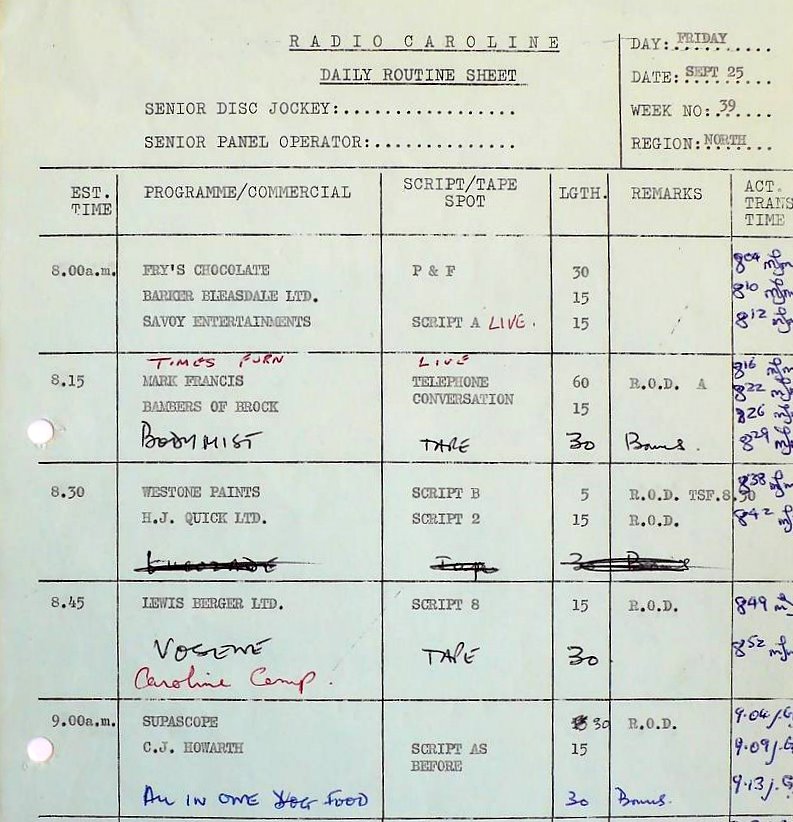

you are actually involved in the studio - if I wasn't actually doing something with my hands, I lit a cigarette. I was getting through about 60 a day. As a background to what we did, obviously it was all (played off) vinyl. Some records

were on tape, a lot of the adverts were on tape, reel to reel tape, some on Spotmaster (cartridges), some were voice-overs, some were voice-over with specific background music... The big advertising spot was on the hour or, if they

couldn't get on the hour, they had the half-hour and, if they couldn't get on the half-hour, the quarter hour and so it went on. So on the hour and the half-hour you were busy. You had to interrupt your programme, have the Spotmasters

cued ready; if there were reel-to-reel adverts, they had to be cued up ready; if you had voice-over adverts, you had to have the scripts ready to read and, of course, as the advert was running you had to log the time because they wanted

to know what time it was actually broadcast. Very important. So for that period of time you were busy, really busy, but it was good fun and you didn't view it as work, you know, it was just something you did.

|

|

| Part of a page from the busy Caroline North advertising log kindly provided by Fred Kooreman. See here for more. |

RC: Did Ronan come out to the ship at any time when you were out there? Or any of the backers like (Jocelyn) Stevens?

AT: They did come out to the ship, some of them, but only very occasionally. There was no real need for them to come out.

RC: Can I ask what sort of money you were on 50 years ago?

AT: I can't remember. I know we had to initially sign on as crew because the Captain paid us. It wasn't bad money and when you think that as we were officially on for 2 weeks and a week off, and everything was all found on board - food

and everything - as much beer and Coke... The Coke was something else. It came from Germany and had much higher caffeine content than the Coke that was available in the UK. If you drank a lot of it in the evening, you couldn't get to

sleep of a night. It was worse than coffee.

RC: There were a number of different company names (involved with Caroline). Can you remember the name of the company that employed you? Was it Planet Productions, or was it Caroline?

AT: I can't remember those things. There were a lot of different companies involved.

|