Paddy Roy Bates was a man of action, even from a young age. At just 15 he joined the International Brigade to fight in the Spanish Civil War and, during the Second World War he rose to the rank

of infantry Major, serving in the 8th India division in Africa, Italy, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere.

|

|

|

Radio Essex QSL card.

|

After the war he threw himself into a number of business ventures, including operating a fishing fleet off the Essex coast. In the mid-sixties he saw the success of Radio Caroline and Radio

London and, being aware of King Radio and Radio City which were operating from anti-aircraft forts in the Thames estuary, he decided to start his own station based on another fort. He picked Knock John which had

been built by the Royal Navy during the Second World War some eighteen miles off Southend, Essex.

Unfortunately someone else had plans for the same fort and, in September 1965, newspapers reported that the two rival groups were battling over possession of Knock John (see press cutting).

The other team was from Radio City. This station was operating successfully from the neighbouring Shivering Sands Fort but they had landed some £3,000 worth of gear on Knock John. They claimed that they wanted to

use the fort as a ‘test-bed’ for new equipment but, as Radio City was at that time involved in merger talks with Radio Caroline, it is more likely that they were planning to start a new station on Knock John once

the deal for Shivering Sands had been completed. However they weren't going to have things their own way. A week later Roy Bates turned up. He led a group of men onto the temporarily deserted fort and declared

squatters rights. Quite naturally Reg Calvert, City's boss, was not prepared to lose his equipment and a feud developed between the two stations. Possession of Knock John alternated between them, with each side

launching attacks on the other and even kidnapping each other's men. The dispute continued for a month but eventually a settlement was reached: City got back its equipment, Roy Bates won possession of the fort.

|

|

|

Knock John. Photo by Martin Stevens, reprinted from ‘Offshore Radio’ by Gerry Bishop, published by Iceni Enterprises.

|

At the end of October 1965, Roy's new station, Radio Essex, commenced transmissions. By January 1966 it was operating 24 hours a day, the first station in Europe to do so. Knock John consisted of a

building on a platform on two hollow cylindrical sea-based legs. These contained the living quarters. Long-deserted, it had been ransacked for anything remotely valuable before Bates and his men arrived. Even the

port-holes and light switches had been removed by scavengers, as had the toilet and washing facilities. The old war-time generator was coaxed back to life and a good deal of work was done to make the fort habitable

again but, even at its best, life aboard was spartan. Although a fort is a more stable base than a ship, it does have one major disadvantage. It is harder to supply. In bad weather a radio ship and a tender can ride the

waves together whereas a fort is rock solid. A supply vessel can be smashed up against it. As a result the DJs frequently endured long periods at sea and often ran short of food and water. No alcohol was allowed and, for

much of the station's life, no television. With just one man's money behind it, the station operated on a shoestring.

Roy Bates, the man himself, reading a commercial for Kent Elms Coachworks. It was recorded in the front room of 33 Avenue Road, Westcliff-on-Sea, the family home which doubled as the station HQ. Tape kindly provided by

David Sinclair (duration 22 seconds)

Roy Bates, the man himself, reading a commercial for Kent Elms Coachworks. It was recorded in the front room of 33 Avenue Road, Westcliff-on-Sea, the family home which doubled as the station HQ. Tape kindly provided by

David Sinclair (duration 22 seconds)

Despite the primitive working and living conditions, there was no shortage of men prepared to endure the hardship for a DJ job on Knock John, most of them young and relatively inexperienced. Radio Essex

proved to be a good training ground and a number of the presenters later went on to jobs with larger stations.

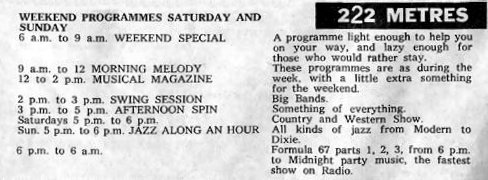

Radio Essex claimed to be the country's first local station. Every advert for a local business would be tagged by the DJ: “...and that's in Essex, of course.” The programmes featured middle-of-the-road music by day,

pop through the night. The transmitter was very low powered and the aerial mast little more than a scaffolding array which meant that, by day, the signal didn't stray far outside Essex and Kent. After dark, however, it went a lot

further, especially after other stations on the same wavelength, 222 metres, had closed down for the night.

|

|

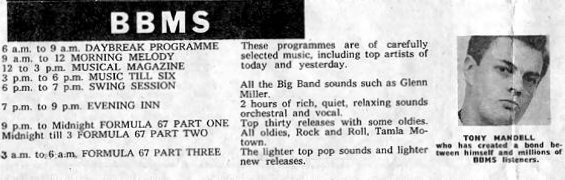

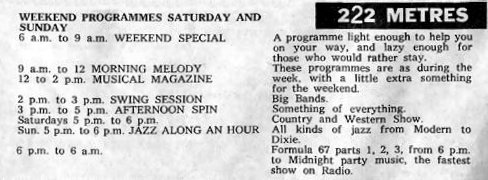

BBMS's final programme schedule, as published in Radio News.

|

On 30th November 1966 Roy Bates was found guilty of broadcasting inside territorial waters in contravention of the 1949 Wireless Telegraphy Act (not the Marine Offences Act, as stated in some of the

newspaper reports linked to below). By this time his station was operating under a different name, BBMS (‘Britain's Better Music Station’). He appealed against the conviction and continued broadcasting but time was

running out. Advertisers were deserting the, now illegal, operation. Money had always been tight but now the DJs began to notice their pay cheques bouncing, or not turning up at all. With no advance warning, BBMS

closed down on Christmas Day 1966. All the equipment was transferred to another North Sea fort, Roughs Tower, which, unlike Knock John, was definitely outside the territorial limit.

Unfortunately Bates was not the only one with plans for Roughs Tower. Radio Caroline boss Ronan O'Rahilly had commissioned a French aviation company, L'Aeronaute Ltd. to convert the fort into a supply base for

Radio Caroline South. They had already removed the wartime superstructure and constructed a helipad. Unfortunately for O'Rahilly, the fort was deserted over Christmas and Bates's men were able to take it over. As had happened

before with the occupation of Knock John, a dispute blew up over ownership and, as before, Roy Bates won. Despite repeated attempts to retake the fort, the Caroline men were eventually forced to give up their claim

(see press cutting).

In September 1967 Roy Bates declared that Roughs Tower was now the independent state of Sealand. He was now known as Prince Roy and his wife as Princess Joan. Passports, stamps and currency were issued for this new

mini-country but, much to the disappointment of Radio Essex / BBMS fans, his radio station never returned to the air.

The Bates family continued to occupy Sealand. There were a number of high profile incidents, including a marriage, a fire and an attempted coup, but with the passing of the years, Prince Roy and Princess Joan became

less involved in the day to day operation, leaving the micro-nation in the hands of their son, Crown Prince Michael. There is much more about the state on Wikipedia and the official Sealand website, and a fascinating story it is too.

On 9th October 2012 Roy Bates passed away quietly in a nursing home in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, having suffered from Alzheimer's for several years. He was 91. Joan died on 10th March 2016, aged 86.

A number of former Radio Essex members of staff have been in touch to pay tribute to their former boss:

Andy Cadier was an early broadcaster on the station, using a DJ name given to him by Roy Bates, Michael Cane: “I always had a very high regard for Roy (and Joan).

Working and living on the fort in quite austere conditions was sometimes pretty tough, but an adventure nonetheless. Prior to joining Radio Essex I had been in the RAF, my father had been an air force officer so working

for an ex-army major had a familiar feel about it. I do remember sitting in Roy's lounge/office while a business call was clearly taking place but, being a Friday afternoon the appropriate person seemed not the be there.

In an exasperated voice Roy said ‘Radio Caroline has a mast ... Radio London has a mast ... and I want one too!’ In fact the cable and scaffolding poles were never replaced, but the GPO were working towards taking

action against the fort based pirates anyway. My thoughts are very much with Roy's family at this time. For myself he will always be remembered as an absolute legend.”

David Sinclair: “Roy always did seem a little larger than life, though I had no idea by how much until I read the biography on the Sealand website (see link below).

What a remarkable guy!”

Mark Wesley, then known as Mark West, expressed similar thoughts: “My radio career owes everything to Roy. I was quite unemployable with no radio potential whatsoever

back then when I was 17. A larger than life character, the world is a smaller place today.”

And from another Radio Essex DJ: “With Roy Bates' passing, so ends an era. Roy was my first boss. Thanks to Roy, the day after A-levels (he wouldn't take me before I'd done the exams) I was out

on Knock John and learning to become a DJ, and a lot else besides. He was also creator of Guy Hamilton - he didn't like my own choice of on-air name so, from his list of favourite names,

I chose ‘Guy Hamilton’, not realising that there was a certain cinematic theme to the list.

Roy was a remarkable bloke. It was impossible not to respect him, though there were times out there that you could have hated him - when your pay didn't arrive, when the boat didn't come, when leave didn't happen - but

what he achieved on next to nothing was remarkable. And because of him our colleagues created a damn good little radio station - shame more people couldn't hear it.

He was probably more famous eventually for creating Sealand than he was for Radio Essex and BBMS but that proved, all over again, his adventurous spirit. Roy taught us young men a lot in 1966 - not just about radio -

and I'll miss him. But his memory will live on, as large as life.

Gerry Zierler, who might have been Gerry Zee but for Roy Bates, but probably would not have got into radio at all.”

Roy Bates's obituary: on the Sealand website, in

The Guardian,

The Independent and

The Telegraph.

News of Roy Bates's death as reported by: The Daily

Mail and the BBC.

There is a 1979 interview with Roy Bates on the Offshore Echos website.

A radio programme about Sealand is available from the BBC.

The BBC Radio 4 series The Last Word commissioned the poet Attila The Stockbroker to write a poem about Roy Bates.

You can hear it here, about 25 minutes into the programme.

|