PETER CHICAGO: Really, from the point that we saw the ship (Ross Revenge) there was no doubt that this was the boat that we would use. It was very, very strongly built, the bows were strengthened for ice breaking

conditions in, sort of, Icelandic waters so it was very, very strong at the bows. The shape of the boat was right; it would be a very stable boat and very suitable to take a tall mast, which of course is what we needed, and the

accommodation was more than adequate. The only thing that frightened me was the size and the complexity of the engine room equipment but, like many things, once you got used to the fact that these things were big but basically no

different from their smaller counterparts, that element of it became less frightening. It was a superb ship and we were lucky to get it for a very good price.

RAY CLARK: What about the journey from Scotland down to Santander? Did you attract attention as you were leaving or did you just sort of say well, we're off? What was the story that you were giving to anybody

that asked?

PC: Well, it didn't quite happen that way from my point of view. We'd seen the boat and Ronan was very enthusiastic and said right, that's it, we'll get the boat, but of course we didn't have the money to go straight out and buy

a boat. Ronan's department was raising the money. This is a skill which Ronan has perfected over the years but there was never really going to be any definite timetable on raising the money and when the boat would be bought. Ronan

sent me over to America to look for transmitters and to buy the broadcasting equipment and at the time that I left to go to Texas, as it turned out to Dallas, we still hadn't purchased the boat. Ronan never had any doubts that we

would find the money and that this would happen. I was again a little bit sceptical but keeping my fingers crossed. And it was whilst I was over in Dallas, and actually lining up the transmitting equipment, that I got an ecstatic

telephone call from Ronan saying “Peter, we've got the boat. The boat is bought and paid for” and shortly after that I had another telephone call to say that the boat was being made ready to go to Spain and a company in

Spain had been found that would build the mast and actually fit the mast to the ship. So I was away in America for a couple of months and all of this was happening back in Europe whilst I was away. I flew back from Dallas, having

bought the transmitting equipment, and went to Spain to find that work had already started. The ship had been dry docked. The shipyard were preparing foundations for the mast so, from what was really just a plan and a dream when

I left to go to America, it had all, you know, it had all started to happen by the time I got back from the States.

|

|

|

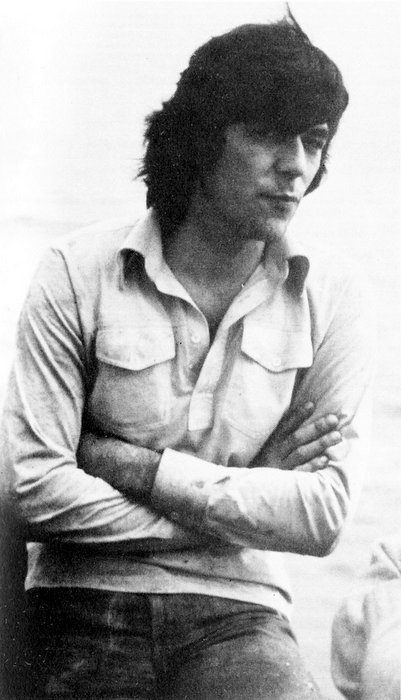

Peter Chicago. Photo from ‘Offshore Echos’ magazine.

|

RC: Even somebody as used to the magic of Caroline and the ups and the downs, you must have got a hell of a kick out of turning that thing back on again in 1983 when it turned up off

the British coast. Can you give us a little bit about the approach to England and the start of it.

PC: When we were in Spain there was a point at which there was a serious disagreement with the Americans who had put up the money to enable the project to go ahead. The whole project was halted and we spent about a year and a half

in Spain so, when we finally got backing, when we had the money to clear the shipyard bills, it was just like a dream come true. I'd spent more than a year, about a year and a half, on the boat beginning to wonder if it was

ever going to leave Spain and it was just so exciting to be leaving.

We had the ship all decked out with flags. An American girlfriend of mine, a lady called Carol, had come over from Texas to be with me and to be with us as the boat was leaving and she decked out flags between the masts,

sort of strung them along lengths of line. The ship really was a spectacle as it left Santander and, because it was in August, in the middle of summer, the beaches were full of trippers. The shipyard where we were was just in the

mouth of an estuary so you had bathing beaches either side of this estuary. The ship was in clear view of two opposing sets of bathing beaches so we had a huge audience as the ship sailed majestically out to sea. There was a

sight-seeing boat that normally did trips around the bay that Ronan had chartered. And Ronan was on the bows of the ship following us as far as he could, with the small ferry starting to be buffeted by the big waves as it headed

out into the open sea. It was just such an exciting moment.

We were towed from Santander to England which was in some ways a disappointment. It would have been exciting to have done it under our own power but what it did mean is that we were able to relax and enjoy the journey. There was

no pressure. There was no worry about whether we'd get there and we were able to more or less enjoy almost a cruise. The Bay of Biscay, which can be very rough, was absolutely smooth and clear. The water was a lovely deep blue

and it was just a wonderful trip between Santander and the English coast. In fact we could tell when we got into the English Channel because the water went from this beautiful clear blue to a sort of a greenish yellowy murky colour

and, the closer we got to our intended anchorage up in the Knock Deep, the murkier the water got until we kind of looked over the side and said, yes, it looks like we've arrived! But it was a fantastically exciting time.

We didn't take any chances in Spain with testing out the transmitters so, when we arrived, we weren't in a position to switch straight on. There was a few days work necessary to get the transmitters ready to work. The first day

that we were there we had about five sight-seeing boats came out and there was almost a flotilla of small boats. You could step from one boat to another. It was almost this great big floating raft with boats all round the Ross Revenge

and it really was a very exciting time. The first day's broadcasting was almost an anti-climax because, after all the excitement that had gone before, the broadcast was never going to live up to all the expectations.

RC: That's super, Peter. Lots of happy times. (Tell me about a less happy one,) the raid.

PC: The raid, yes. The first I heard about any impending trouble was an announcement on the Radio Caroline news. I'd actually been on shore leave and there was a call, I think, earmarked for the attention of the office added on

to the end of the Caroline news which indicated a problem. We had a telephone out on the boat at this time. It was quite a recent addition to the ship's facilities and certainly made life a lot more pleasant for those on board.

I was able to telephone the boat and find out exactly what was going on. Apparently a British boat, chartered by the Department of Trade or the DTI, had gone out to the ship and invited the crew to stop broadcasting and leave the

ship under pain of some unspecified threat. Well, needless to say, nobody was prepared to just walk away from the boat but they had been given to understand that if they weren't prepared to stop broadcasting that something

more serious was going to happen the following day. It all appeared rather vague and odd and I realised that the best thing I could do was to get out to the boat.

Well, at this time I had a small ten foot inflatable dinghy or rubber boat with a small engine. The weather was quite good so that night I remember that with Carol, my wife at the time, we went out for a drink, had a quiet drink

in the pub and then loaded the dinghy into the car and drove down to Broadstairs to the small harbour there, inflated the boat on the quay hoping that no passing police car was going to take too much of an interest in these

proceedings and, in short, put this boat over the side and I went out from Broadstairs to the ship. It was quite exciting. I'd never attempted to get out to the boat, you know, just on my own and in a small dinghy before but it

was a very good night for it, a clear sort of moonlit night, and the sea was reasonably calm.

I got out to the boat in the middle of the night and got a little bit more detail to the story but nobody really knew what was going to happen. We were told that the Department of Trade were going to return at eleven o'clock in the

morning to receive an answer; in other words, were people prepared to close the radio station down and leave the ship or not? So we waited and at eleven o'clock a boat, I believe it was called the Landward, came into sight.

I think it was a fairly misty day, from my memory, so we didn't see them until they were fairly close, and they hinted that the boat was being used or that people involved in the operation were involved in much more serious crime.

That was the first angle that came across: you know we realise that you're only out here broadcasting in all innocence but we have to tell you there are much more serious matters involved and your offices in Holland and

England have all been raided.” Well, I knew that this was rubbish because I knew all of the people involved very intimately. I mean, Ronan himself, he's Irish, there've been suggestions by some people that there were connections

with IRA terrorism. Well nothing could be further from the truth. Ronan is the most peace-loving, genuine person who would never even dream of any possible connection with anything like that. There's been suggestions that the boat

was used for drug-running or laundering money but all that was just because people couldn't believe the truth which was that we enjoyed doing what we were doing and that we weren't making much money at it but we did enjoy the

broadcasting and the freedom of being out there.

|

|

|

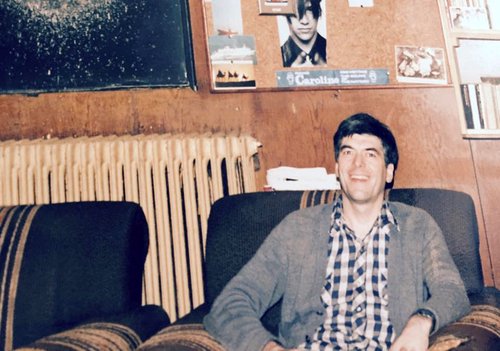

Peter Chicago relaxing on the Ross Revenge. Photo courtesy of Caroline Martin. More of her photos here.

|

Well, when they saw that these implied threats and, you know, “you don't know quite what you've got mixed up in but, you know, be good boys and leave the boat and nothing further will happen to you”,

when that angle didn't work they said “Well we have to tell you that phase two of the operation is due to come into operation soon and, you know, if you're not prepared to sort of leave the boat now you'll have to take your

chances.” Well they left and I suppose it was about half an hour later a much bigger boat came into view. At first I thought it was a tug but it was a Dutch boat, the mv Volans, which belongs to Rijkswaterstaat which is the,

I suppose, Dutch water authority or almost water police, it's an official department anyway. And they were coming straight towards us and it was quite obvious that they were intending to come alongside. I called them on the radio to

try to find out what the intentions were and they ignored the calls. I called North Foreland Radio to try to communicate with them to say that we were under threat but again North Foreland Radio ignored the calls. Before I had a

chance to do anything else, the boat had actually come alongside so, at that point, I left the bridge and went downstairs to try and stop anything further happening.

There were uniformed, well, they appeared to be police officers, Dutch police, on board. One of the police officers started to come over the side. I pushed him back and again he made another attempt to sort of come over and again I

pushed him back. At that point he started to draw a pistol and again I didn't back off and he changed his mind and the next thing I knew I'd been hit pretty hard on the chin, hard enough that I blacked out for a few seconds. By the

time I came to he had actually boarded the boat and by this time there were several other uniformed officials on board and really that was it, the boat had been boarded. The spokesperson was a man called Mart Roumen who works

for the equivalent of the DTI over in Holland and he explained that they were taking action under Dutch law which, in his own words, entitled them to come out and seize any transmitting equipment that had been used to make broadcasts

towards Holland. Their instructions were to take the equipment intact so he sent some technicians down below and, within a couple of minutes, they'd come back up on deck again and said well, this was completely impossible. It was

going to take them about two weeks to dismantle the equipment. There was more discussion in Dutch and finally I think Mart Roumen made communication with his superiors back in Holland and they decided that they were going to take

the major components out of the transmitters and, as we later discovered, just about everything else that they could get their hands on.

They said that they were going to remove things intact but, as the day progressed, more and more damage was being done and the components they did take out of the transmitters, a lot of them were smashed or cut out. There

was an awful lot of broken porcelain, wires hacked through and even transformers, which had been too large to remove, were damaged by sort of chipping at them with pointed chipping hammers. In other words, the ship was being completely

gutted of all viable broadcasting equipment. They even turned their attention to the ship's generators. They had put one of the generators out of action - again by using a hammer on the pump and actually smashing the pump housing -

but, before that had got too far advanced, I pointed out to them that these were the generators that supplied power to the whole boat and that they were actually putting the boat itself and anybody on it in danger by disabling the

power plant. They did at that point stop but not, as I say, before it was too late for one of the generators which had already been disabled.

The whole thing was just an extremely unpleasant and really soul destroying experience. I mean, I had been instrumental in putting the whole of the transmitting installation together. I mean not just on my own but, even in the studios,

I had put a lot of the woodwork together, certainly planned the layout of the studios and, to see it all destroyed piecemeal and, as I say, quite often just deliberately damaged.... If something couldn't be removed easily then it was

either damaged in such a way that it was no longer of use or ripped out leaving maybe the bottom of a cassette deck bolted down to the desk just in order to remove the top. So it was really a horrible day. The only slightly good thing

that did happen was that, over the course of the day, I tried my best to argue the Dutch technicians out of what they were doing and I think I was able to appeal to their better nature to the extent that, at five o'clock in the

evening, they announced that they were going to have a break and, you know, go for a tea break back on their own ship. This to me was a pretty clear signal from them saying “Well, look, if you've got any sense go down below and

take as much as you can and put it away and at least have something to get back on the air with.” I mean, I'm sure it was quite deliberate, a nudge, a nod and a wink and all the rest of it - and, of course, we did take the

opportunity of putting enough equipment to get one of the radio transmitters back on the air again. It's the only reason that we were able to come (back) on so quickly.

|

|

|

The shattered remains of the Radio Caroline studio after the Dutch raid. Photo by M.Kuske from ‘Offshore Echos’ magazine.

|

RC: Twenty years of it. Why did you do it? Why did you stay with Caroline?

PC: I suppose because, after a while, it seemed to me that - this may be rather conceited on my part - but I did believe that nobody else was going to be able to keep it going. I have, I suppose, over the years got used to working

with very limited facilities and I just know, from fellow engineers that I have worked with, that many of them wouldn't even consider working under those conditions. So I suppose I figured that, if I gave up on Caroline, that the

whole thing would just grind to a halt. I mean, it's not that I'm the best engineer in the business. It's probably that I'm the best one that was willing to go on under the circumstances that pertained. I suppose I could have made

a lot of money elsewhere, and I'm not pretending the money wouldn't have been important, but I suppose there was something, there was a magic with Caroline, that made it all worthwhile.

RC: Would you do it again?

PC: I think I would do it again because there's been some wonderful times in that twenty years and times that I'm sure could have only, only happened in the way they did and it's just been... It has been a wonderful experience. I

feel that I've achieved something in a way that I couldn't have done in an ordinary sort of a job.

Our thanks to Ray Clark for providing the interview, to Pauline Miller for transcribing it and to Marcel Strücker for pointing out a mistake, now corrected.

Back to the previous page.

Another of Ray's interviews - by letter - with Gordon Cruse, over the page.

|